PORTOBELLO

CARNIVAL FILM FESTIVAL 2008

1

Portobello Carnival Film Festival 2008

2 Lord

Holland’s Slavery to Work Scheme

3 The

Notting Dale Gypsies

4 Portobello

Busker Parades

5 1966

London Free School Michaelmas Fayre

6 1968

Interzone International Times Fair

7 1977

Two Sevens Clash Punky Reggae Party

8 1983/4

Aswad Live And Direct Carnival

9 1995

Hugh Grant Mas and Mayhem

PART 4

Portobello

Busker Parades

Between the wars Portobello

Road was noted for busker parades and impromptu Bedknobs

and Broomsticks-style carnivals. As recalled in Portobello:

Its People, Its Past, Its Present, a busker group featuring

saxophone, trumpet, cornet and banjo players had a street

parade from the Sun in Splendour pub up to the Gas Works.

There was also a pianist and singer in the back of a

van, a concertina player touring the pubs, and ‘Silly

Henry’, an early breakdancer who’s sound-system

consisted of a gramophone in a pram. The streets of

Ladbroke Grove were also the scene of regular Catholic

processions.

Wilsham Street George VI Coronation Street Party 1936

1941 Bedknobs and Broomsticks Carnival

The Disneyland Carnival scene in Bedknobs and

Broomsticks, set in 1941, features Cockney, Scottish

and Asian turns and a West Indian steel band. It is

possible that West Indian servicemen would have been

on Portobello during the war, but steel bands were only

just coming into existence in the West Indies; using

US army oil drums to get round British colonial laws

banning the beating of African drums.

Rillington Place Elizabeth II Coronation Street Party

1953

1958 Rock’n’Roll Fascist Carnival

(Link to 58 Remembered – 50 Years On and Historytalk)

Over the August bank holiday weekend of 1958,

a local mob reinforced by Teddy boys indulged in a dictionary

definition Carnival of ‘riotous revelry: reckless

indulgence in something’, if not much bloodshed

then plenty of window smashing, spurred on by fascists

in an echo of the Nazi Kristallnacht 20 years earlier.

In Beyond the Mother Country, Edward Pilkington calls

Notting Hill during the riots ‘a looking-glass

world’, in which everyday objects like milk-bottles,

dustbin-lids and car tyres were transformed into ammunition,

shields and barricades; like the battle of Portobello

Road, without guns or much serious injury, in GK Chesterton’s

The Napoleon of Notting Hill.

The anti-apartheid bishop Trevor Huddleston concluded

on the riot, when he was based in Holland Park: ‘If

it should lead, as it still may, to a radical searching

of the conscience on the part of ordinary citizens,

then much good will have come out of evil.’ Like

the Gordon riots of 1780, which started anti-catholic

and ended up proto-communist, the 1958 Notting Hill

riot can be seen in a positive light, dispelling the

mother country myth and creating the reality of multicultural

Britain. United in their resolve to stay put, Jamaicans,

Trinidadians, small islanders, even Barbadians (who

were traditionally police) and Africans came together

to forge a new black British Afro-Caribbean identity.

Ironically, the main inspiration of Notting Hill Carnival

wasn’t old English fairs or Caribbean carnivals,

but the anti-black British riot. By the 50th anniversary

of the arrival of the Empire Windrush, and the 40th

of the riot, in the Windrush book charting ‘the

irresistible rise of multi-racial Britain’, Mike

and Trevor Phillips portrayed 1958 as virtually a positive

rite of passage, a ‘sounding board for popular

discontent’ that brought racial prejudice out

into the open, along with white working class exclusion

from mainstream society. The traditional random reckless

revelry was noted, with black and white children playing

together in the streets between incidents; getting close

to the argument that it doesn’t count as a real

race riot. Colin MacInnes’s vision in Absolute

Beginners of a ‘cheerfully anarchic’ music

hall-style Carnival, with hooray Henrys, debutantes

and hustlers dancing in the rain, was pretty much how

it turned out in the 90s.

The Road Made To Walk on Carnival Day

The 1958 origin of Notting Hill Carnival was

summed up by Darcus Howe, the radical 70s organiser,

in his interview for the Mas and Mayhem Carnival history

project: “Once you live a huge moment of history,

you know exactly how history is made. Once you live

in a big moment, otherwise you think somebody orchestrated

it or somebody started it. If you want to look for somebody

who started Carnival you’ll never find an individual

– that’s out of the question, there is no

entrepreneur or impresario who called it into being.

It looked like we needed it and the road was there and

some guys had some instruments in a pub and that was

it. That was it! I think what was important was the

place because the first Notting Hill riots took place

on August bank holiday, so I don’t think it’s

a coincidence that we had it in Notting Hill. I think

Notting Hill has always been, even before the Carnival

started, explained to me as liberated territory, a place

where you stood up for your rights and where Kelso Cochrane

lost his life. That I can accept quite easily because

the coincidence is too bizarre. It just developed.”

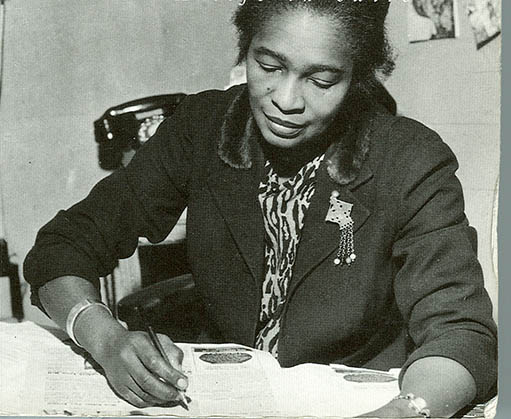

1959 West Indian Gazette Caribbean Carnival

The London Caribbean Carnival was officially

founded in 1959 by Claudia Jones, the Trinidad-born

US civil rights activist who edited the West Indian

Gazette. The first ‘indoors Carnival’ (or

West Indian Gazette Carnival) took place on January

30 1959 at St Pancras Town Hall, Euston. Cleo Laine

topped the bill which included the Mighty Terror singing

the calypso ‘Carnival at St Pancras’. The

nearest the indoors Carnival came to Notting Hill was

the Town Hall on Kensington High Street in 1960. In

April ’59 there was a West Indian steel band on

the first CND march to Aldermaston.

Marcus Garvey Birthday Skiffle Carnival

The Carnival stalwart Baron Baker remembered

a late 50s skiffle-Carnival in St Stephen’s Gardens

on Marcus Garvey’s birthday anniversary; featuring

Totobag (from the Caribbean café at 9 Blenheim

Crescent), King Dick, Gash Boots, Benji and himself,

on bongos, guitar, graters, bottles and boxes; but not

whether it was before or after the riot. This Carnival

tendency, at least, was confirmed by Tommy Farr of the

St Stephen’s Gardens tenants’ association,

who recalled ghetto fabulous West Indians turning up

at the street’s Gigi blues club.

In the early 30s, as Rastafarianism was founded in Jamaica,

Marcus Garvey came to London after the collapse of his

Black Starliner Afro-utopian plans; to reputedly be

one of the first West Indian residents of Powis Square

(formerly known as ‘Little (east) India’).

Marcus Garvey died in west Kensington in 1940 and was

buried at Kensal Green cemetery, for 24 years; then

he was re-interred in Kingston as Jamaica’s first

national hero. After the ’58 riot, his widow Amy

Ashwood-Garvey founded the Association for the Advancement

of Coloured People on Bassett Road, and worked with

the Carnival founder Claudia Jones.

1959 Kelso Cochrane Funeral Procession

On May 17 1959, a West Indian man called Kelso

Cochrane was stabbed to death by a gang of white men

on Southam Street in Kensal. This was when the fascist

leader Oswald Mosley was standing as the Union Movement

candidate for North Kensington in the ’59 election,

and holding street meetings around the area. He subsequently

appeared at the murder scene on Southam Street. But,

rather than start another riot, the killing of Kelso

Cochrane turned the tide against the fascists, and started

Notting Hill Carnival.

As Mosley was blamed for bringing further disgrace on

the area, on June 11 over a thousand black and white

people followed Kelso Cochrane’s funeral cortege,

in what has been described as a proto-Carnival procession,

along Ladbroke Grove to Kensal Green Cemetery. Mike

Phillips called it ‘the great event which ended

the 50s and began the West Indian decade of Notting

Hill.’

1963 Ladbroke Grove I Have A Dream March

In the early 60s the basic ingredients of the

modern Notting Hill Carnival were emerging, though not

necessarily in Notting Hill. On August 31 1963, Claudia

Jones’s diary featured a procession of her Committee

of Afro-Asian Caribbean Organisations, in solidarity

with the Washington Martin Luther King “I have

a dream” march, from Ladbroke Grove station to

the US embassy in Grosvenor Square.

1960s Indoors Carnival

After Claudia Jones’s death, Victor Crichlow

(brother of Frank, of El Rio and Mangrove fame), Scrubbs

and Bynoe took up from where she left off with steel

band dances, at such venues as the Lyceum on the Strand

and Porchester Halls in Bayswater. There was even ‘a

tentative alliance with the gay movement’, as

Darcus Howe put it, at the Coleherne pub in Earl’s

Court where Russell Henderson, Sterling Betancourt,

Vernon Fellows and Nickidee played lunchtime jazz sets.

1964 A Hard Day’s Night Parade

Back in North Kensington the community activist

Rhaune Laslett joined forces with the steel band leader

Selwyn Baptiste to teach children to play the pans at

the Wornington Road adventure playground (now the Venture

Centre) off Golborne Road. But, as far as any evidence

goes, in the years of the media myth first Notting Hill

Carnival, 1964 or ’65, nothing happened. Apart

from, that is, when Ringo Starr went ‘parading’

along All Saints Road, and was joined by the other Beatles

in Notting Dale in A Hard Day’s Night.

5 1966

London Free School Michaelmas Fayre

|