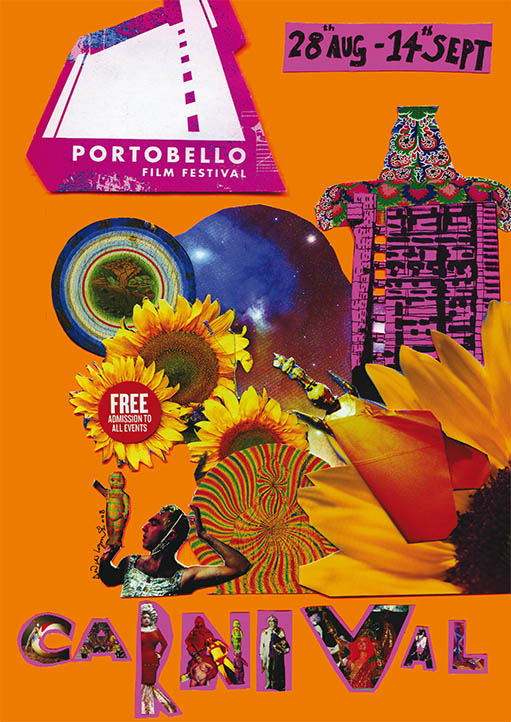

PORTOBELLO

CARNIVAL FILM FESTIVAL 2008

1

Portobello Carnival Film Festival 2008

2 Lord

Holland’s Slavery to Work Scheme

3 The

Notting Dale Gypsies

4 Portobello

Busker Parades

5 1966

London Free School Michaelmas Fayre

6 1968

Interzone International Times Fair

7 1977

Two Sevens Clash Punky Reggae Party

8 1983/4

Aswad Live And Direct Carnival

9 1995

Hugh Grant Mas and Mayhem

PART 1

PORTOBELLO CARNIVAL FILM FESTIVAL 2008

Carnival was traditionally a Catholic festival taking

place on Shrove Tuesday or Mardi Gras before the beginning

of Lent, the period of fasting and abstinence. It is

a time when all caution is thrown to the winds, there

is much festivity and feasting, the Lords of Misrule

are celebrated in a wild party prior to a month or more

of self denial. It eventually became an opportunity

for slaves in the New World to temporarily throw off

their shackles.

Historically such delirious excesses go back beyond

Christianity and represent a very real need for people

to let their hair down, to be free albeit briefly from

the restraints of polite society, to make the dreary

day to day life of the rest of the year more bearable.

It was the theme of the fairs and festivals in the middle

ages, and the pagan orgies of Greece and Rome.

Its other contemporary roots lie in the magical hallucinatory

rituals of Africa and America, a powerful race memory

preserving vestiges of atavistic cultures going back

to the dawn of time displaced and ravaged by the slave

trade and colonialism. Notting Hill Carnival itself

is a direct descendant of the Carnival in Trinidad,

from where many migrants came to the UK and the Second

World War.

The art of Carnival, as celebrated in Brazil, New Orleans

and Notting Hill, can also trace many of its influences

back to the original Masquerade, the Carnival in Venice:

the dressing up and cross-dressing, the masks, the processions,

the circus element, the spectacle, the music, Punch

and Judy, Harlequin and Columbine, Commedia Del Arte,

the Comedy of Art.

For this is a joyous art form: it is happy, it is colourful,

it is exuberant, it is satirical, it doesn’t take

itself too preciously, it is the art of the people.

It doesn’t sit on its arse in museums, it gets

out in the streets, it is free, which matches the central

theme of the Portobello Film Festival, it makes people

happy. Even the morbid theme of the Mexican Day of the

Dead, another third world carnivalist collision between

church and paganism, is subverted by comedy and joy.

Portobello Film Festival proposes to weave together

some of the above themes that have contributed to the

phenomenon of Carnival and present them as a 21st century

compliment to the Notting Hill Carnival 2008.

Local historian Tom Vague

examines the origins, definitions, influences, traditions,

legends and myths of Notting Hill Carnival (Vague 48)

The Goose Fair Origin

The London Free School Fayre in 1966, the first modern

Notting Hill Carnival, is said to have been inspired

by an earlier Goose Fair or Fayre, in what could be

hippy confusion with the renowned Nottingham Goose Fair.

As described in Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase

and Fable, Goose Fairs were ‘formerly held in

many English towns about the time of Michaelmas, when

geese were plentiful. That still held at Nottingham

was the most important. Tavistock Goosey Fair is still

held, though geese are seldom sold, goose lunches are

available.’ In another Goose Fair coincidence,

the 1966 procession began on Tavistock Road in late

September.

Michaelmas Day, the festival of St Michael and All Angels,

is September 29, a former Quarter-day when rents were

due, magistrates were chosen and geese were presented

to landlords from ancient times. In another tradition,

Elizabeth I is said to have started the custom in 1588.

Whilst dining on goose with Sir Neville Umfreyville

on her way to Tilbury, she made the toast “Death

to the Spanish Armada”, whereupon news arrived

of the weather assisted demise of the invasion fleet.

However this happened in July.

The May Events

During the reign of Elizabeth I, according

to the Puritan Phillip Stubbes’, throughout the

land in ‘May, Whitsunday, or other time, all the

young men and maids, old men and wives, run gadding

over night to the woods, groves and hills, and mountains,

where they spend all the night in pleasant pastimes;

and in the morning they return, bringing with them birch

and branches of trees, to deck their assemblies withal…

But the chiefest jewel they bring from thence is their

May-pole, which they bring home with great veneration.

‘They have twenty or forty yoke of oxen, every

ox having a sweet nose-gay of flowers placed on the

tip of his horns, and these oxen draw home this May-pole

(this stinking idol, rather), which is covered all over

with flowers and herbs, bound round about with strings,

from the top to the bottom, and sometimes painted with

variable colours, with two or three hundred men, women

and children following it with great devotion. And thus

being reared up, with handkerchiefs and flags hovering

on the top, they straw the ground round about it, set

up summer haules, bowers, and arbors hard by it. And

then fall they to dance about it, like as the heathen

people did at the dedication of the idols.’

In Notting Hill in Bygone Days the area was noted as

a venue of May dances and Jack in the Green wickerman

processions. JG Frazer described the Jack in the Green

leaf-clad mummer in The Golden Bough as a ‘relic

of tree-worship in modern Europe’, featuring a

chimney sweep in ‘a pyramidical framework of wickerwork’

covered in holly and ivy and crowned with flowers and

ribbons, at the head of a May day parade of fellow chimney

sweeps collecting gratuities

Carnevale, Fasching and Mardi Gras (Fat Tuesday)

In the Oxford Concise Dictionary, Carnival

is defined as the festivities in Roman Catholic countries

in the half-week or week before Lent, or riotous revelry;

reckless indulgence in something, carnival of bloodshed,

etc. The Latin term ‘Carne Vale’ means ‘farewell

to the flesh’ or ‘flight of the flesh’,

before the 45 day fast of Lent from Ash Wednesday till

Easter in March. The term dates back to the 16th century

and is derived from the Latin carne, carnovale, carnelevarium,

from caro – flesh and levare – put away.

The Carnevale in Venice dates back a thousand years,

and the Germans had a dubious sounding ‘Fasching’

carnival-style festival. The Paris Mardi Gras ‘Fat

Tuesday’ festival featured an ox crowned with

a fillet (presumably a ribbon or head-band rather than

a piece of meat or boned fish), which was paraded through

the streets with mock priests and a tin band, imitating

a Roman sacrificial procession.

Caribbean and New World Carnivals

The French took their Roman Catholic carnival

festival to Trinidad, in the form of dinners, balls

and fetes where slave masters dressed as slaves with

blackened faces at the culmination of the elite French

Creole social season. In Brazil, Cuba and Barbados ‘Crop

Over’ Carnivals developed without the French influence.

In New Orleans the first Mardi Gras krewes formed out

of aristocratic secret societies.

After the 1833 Emancipation Act abolished slavery in

the British empire, West Indians celebrated their liberation

with annual carnivals, using the European Catholic format

with an African cultural spin. The most famous in Port

of Spain, Trinidad, acquired an anti-slavery dimension

in the mas playing role reversals of former slaves mocking

former slave masters by dressing up, or masquerading,

in devil costumes. The ‘Canne Brulee’, cane

burning festival, celebrated with stick fights, fetes

and rum drinking, developed into mass carnivals mocking

authority.

The Porto Belo Carnival and the War of Jenkins’

Ear

By the 1720 Treaty of Utrecht Assiento, Britain

was transporting 5,000 African slaves a year to South

America. To curtail any further British trade guard-ships

patrolled the Spanish Main. In the late 1730s a war

over shipping rights was sparked by an incident in which

a British captain, suspected of smuggling, reputedly

had his ear torn off by a Spaniard. ‘The War of

Jenkins’ Ear’ began with a small fleet under

the command of Admiral Edward Vernon taking the Spanish

stronghold of Porto Belo (now in Panama). In all likelihood,

it was in celebration of this victory that the local

farmer Abraham Adams named his farmhouse, and hence

the lane/road to it. At the same time in New York there

was an uprising of Africans, Irish and Spanish known

as ‘the Slave Plot’ of 1741, brought about

by recruitment for the British war.

With some historical irony, in the 20th century the

former Portobello farmland became home to Afro-Caribbean,

Irish and Spanish communities, while Vernon Yard on

Portobello Road hosted the offices of Virgin Records

including the Frontline reggae label. Meanwhile back

in Porto Belo, Panama, the descendants of escaped African

slaves hold a proper Lent carnival in March.

The World Turned Upside Down

In the King Mob ruled 18th century of more

or less non-stop riots, rebellions and carnivalesque

revelries, English fairs with mock mayor ceremonies

were closer to pagan king killing rituals than Catholic

carnivals. William Hogarth’s 1761 ‘A View

from Cheapside’ depicts rowdy festivities featuring

a black horn player. In Old London, Edward Walford wrote

of hangings at Tyburn, ‘execution day, as it was

termed, must have been a carnival of frequent occurrence.’

John Wallis described a Northumberland Christmas ritual

in 1769, in which ‘young men march from village

to village, and from house to house, with music before

them, dressed in an antic (odd, grotesque) attire, and

before the entrance of every house entertain the family

with the antic dance with swords or spears in their

hands, erect and shining. This they call the sword-dance.

For their pains they are presented with a small gratuity

in money, more or less, according to every house-holder’s

ability. Their gratitude is expressed by firing a gun.’

Such activities were duly suppressed and more or less

ended by a combination of the Industrial Revolution,

the Protestant work ethic, labour laws and land enclosure.

part 2:

Lord Holland’s Slavery to Work Scheme

|