PORTOBELLO

CARNIVAL FILM FESTIVAL 2008

1

Portobello Carnival Film Festival 2008

2 Lord

Holland’s Slavery to Work Scheme

3 The

Notting Dale Gypsies

4 Portobello

Busker Parades

5 1966

London Free School Michaelmas Fayre

6 1968

Interzone International Times Fair

7 1977

Two Sevens Clash Punky Reggae Party

8 1983/4

Aswad Live And Direct Carnival

9 1995

Hugh Grant Mas and Mayhem

PART 3

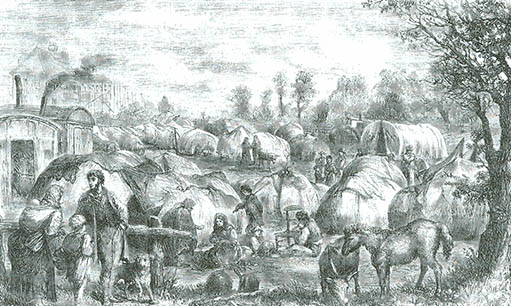

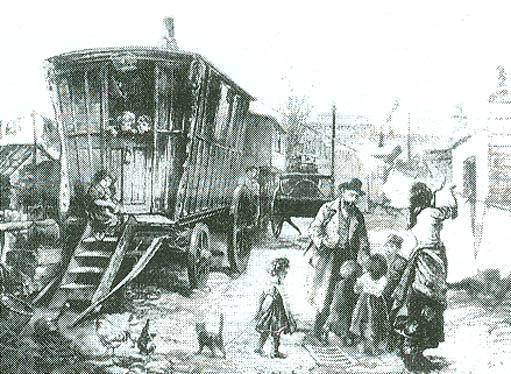

The Notting Dale Gypsies

In the final stages of urbanisation, the Notting Dale

gypsies were integrated into the community by a combination

of do-gooding and health restrictions. The 1870s gypsy

street in Mary Place was described by George Barrow

as ‘chock full of crazy, battered caravans of

all colours… dark men, wild looking women and

yellow faced children.’ The local king of the

gypsies, Mesach, Thomas or Old Hearn, was a 90 year

old veteran of the Napoleonic wars who had travelled

the country chair-bottoming before settling in a comfortably

converted advertising van between two trees.

1870s Portobello Market Carnival

By the early 1870s, Portobello had succeeded

the original local market on Norland Road, and its ‘general

London notoriety’ was assured for ‘cheery

cries, surging crowds and heavily laden stalls.’

Sir William Bull MP wrote of the early market in ‘Some

Recollections of Bayswater 50 Years Ago’, for

the Bayswater Chronicle in 1923: ‘Columbus discovered

Porto Bello in 1502. We discovered Portobello Road about

370 years later. Carnival time was on Saturday nights

in the winter, when it was thronged like a fair…

in the side-streets were side-shows’ including

vendors of patent medicine, conjurors and itinerant

musicians.

Wormwood Scrubs Fair

In the late 19th century Little Wormwood Scrubs

hosted fairs with roundabouts and drinking booths, and

Sunday morning bare-knuckle bouts; one of which resulted

in a local gypsy being tried for murder but found innocent.

According to Florence Gladstone in Notting Hill in Bygone

Days, ‘in the summertime the proceedings every

Sunday evening were so disorderly that respectable people

could not walk in that direction. It was only after

the Wormwood Scrubbs regulation bill was passed in 1879

that this corner settled down to an orderly existence.’

This could be the fair referred to by the 1966 Carnival

founder Rhaune Laslett. In the opening chapter of Abner

Cohen’s Masquerade Politics, ‘A Resurrected

London Fair’, she’s quoted as saying it

was ‘a revival of the Notting Hill annual fair

that had been traditionally held in the area until it

was stopped at the turn of the century.’

1880s Canboulay Riots

In Trinidad in the 1880s there were major clashes

between the colonial police and carnival revellers in

the Canboulay riots. Canboulay fights between rival

bands, where sticksmen traditionally resolved personal

differences, began to take on revolutionary significance.

After a Carnival riot in San Fernando in 1882, when

police tried to stop playing early, drums were banned

from the Trinidad Carnival for being barbaric, and to

prevent them becoming a focal point of mounting racial

tension.

The Rio Carnival and New Orleans Mardi Gras

The Rio Carnival started up in 1888 after the

abolition of slavery in Brazil and a severe drought

which resulted in a former slave community in the city.

In New Orleans in the early 20th century the first black

krewe paraded with a King Zulu character mocking the

white Carnival royalty with a banana stalk sceptre and

lard-can crown. Back in Brazil the Rio samba schools

formed in the 1920s and 30s.

1904 Battle of Portobello Road

GK Chesterton’s local literary classic

The Napoleon of Notting Hill (written at the turn of

the 20th century) features a fairytale battle, more

of a riot really, at the beginning of Portobello Road.

Prophetically, Notting Hill wins the war but is changed

for the worse and loses the final battle to the rest

of London:

“As we walked wearily round the corner, something

happened. When something happens, it happens first,

and you see it afterwards. It happens itself, and you

have nothing to do with it. It proves a dreadful thing

– that there are other things besides one’s

self. I can only put it this way. We went round one

turning, two turnings, three turnings, four turnings,

five. Then I lifted myself slowly up from the gutter

where I had been shot half senseless, and was beaten

down again by living men crashing on top of me, and

the world was full of roaring, and big men rolling about

like ninepins.” Buck looked at his map with knitted

brows. “Was that Portobello Road?” he asked.

“Yes”, said Barker, “Yes, Portobello

Road – I saw it afterwards: but, my God –

what a place it was!”…

“Notting Hill has fallen; Notting Hill has died.

But that is not the tremendous issue. Notting Hill has

lived.” “But if”, answered the other

voice, “if what is achieved by all these efforts

be only the common contentment of humanity, why do men

so extravagantly toil and die in them? Has nothing been

done by Notting Hill that any chance clump of farmers

or clan of savages would not have done without it? What

might have been done to Notting Hill if the world had

been different may be a deep question; but there is

a deeper. What could have happened to the world if Notting

Hill had never been?” The other voice replied;

“The same thing that would have happened to the

world and all the starry systems if an apple-tree grew

6 apples instead of 7; something would have been eternally

lost. There has never been anything in the world absolutely

like Notting Hill. There will never be anything like

it to the crack of doom. I cannot believe anything but

that God loved it as he must surely love anything that

is itself and unreplaceable. But even for that I do

not care. If God, with all his blunders, hated it, I

loved it.”

1914 Anti-German Electric Cinema Riot

In the 1909 Interesting History of Portobello

Road, Edward Woolf chanced fate stating that ‘orderliness

exists in the extreme, and a police charge in Portobello

Road on a Saturday night is the rarest occurrence.’

At the outbreak of World War 1, in the next Notting

Hill race riot the Electric Cinema was attacked by a

mob who accused the German manager of signalling to

Zeppelins from the roof.

Bangor Street Rag Fair

Bangor Street, the most notorious road of the Notting

Dale ‘Special Area’ slum (on the site of

Henry Dickens Court), was known as ‘Do as you

like Street’, a place where ‘no one left

their door closed’, and the venue of the Rag Fair.

At the turn of the 20th century, the local district

nurses were reported ‘valiantly holding their

own in spite of the disturbance caused by nightly brawls

and the noisy and unsavoury Sunday markets.’

Valerie Wilson recalled in an interview by the Notting

Dale Urban Studies group: “They used to threaten

us – don’t go up rag fair and the first

thing we did when we got outside, we forgot all about

it and went straight through rag fair… that was

really like a film show, they used to hang old bits

of clothing on the railings… the street would

throng with people… there was a group of men who

came out the war and they were all ex-servicemen, big

tall strong men, and they couldn’t get work, so

they formed this group and they dressed up in tulle

like a fairy in a pantomime and they made their faces

up, hideous like white faces and red rouged cheeks and

red false curls and they used to dance and people, children

and grown-ups, they formed a circle or square and people

would throw a penny in.”

As an example of local characters ‘who make the

most of the notoriety of their surroundings’,

and the slumming tradition, a Bangor Street urchin recounted

some “hunderworld business”, in which “the

char-a-banc blokes bring the toffs to the end of the

street, they pay 6 shillings and 6 pence a time, could

you believe it? When the tic-tac man gives the word

then father sloshes mother, she screams “Murder!”

and I slosh father, then Ennis over the way sloshes

his old girl and a free fight starts all around…

Dad gives me a sprasy (6 pence).” Bangor and Wilsham

Street also hosted more respectable Coronation street

parties.

1930s Notting Hill Carnival

The 1930s Notting Hill Carnival, or the Princess

Louise Hospital Carnival, consisted of a procession

from the hospital along Pangbourne Avenue, Latimer Road,

Silchester Road and Clarendon Road to Kensington Gardens.

The 1934 Carnival line-up featured a girl with traffic

lights on her head, Britannia, a Scotsman, a milkmaid,

bellboy, clown and a blacked up youth. This could be

the fair before the last war referred to by Michael

Horovitz as being revived in the 1966 London Free School

Fair.

4 Portobello

Busker Parades

|