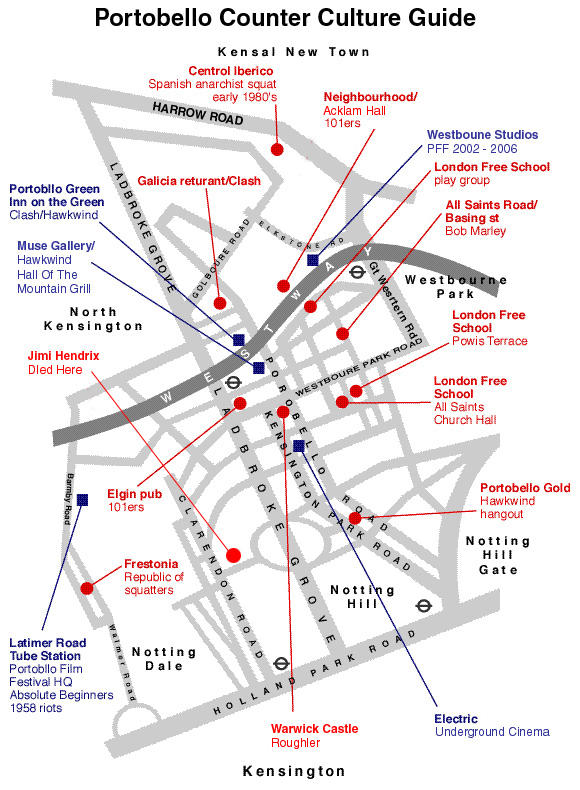

PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL 2006

Counter Culture Portobello

Psychogeographical History

by Tom Vague.

Back to main

page

Part 1 - ABSOLUTE

BEGINNERS

Part 2 - THE LONDON FREE SCHOOL

Part 3 - HAWKWIND

Part 4 - BOB MARLEY AND THE WAILERS

Part 6 - FRESTONIA

Part 7 - SKETCHES OF SPAIN

5 STRUMMERVILLE

‘When I think of the punk years, particularly 1977, I always think

of one particular spot, just at the point where the elevated Westway

diverges from Harrow Road and pursues the line of the Hammersmith and

City tube tracks to Westbourne Park Station. From the end of 1976, one

of the stanchions holding up the Westway was emblazoned with large graffiti

which said simply, ‘The Clash’. When first sprayed the graffiti

laid a psychic boundary marker for the group – This was their

manor, this was how they saw London.’ Jon Savage ‘Punk London’

‘All across the town, all across the night, everybody’s

driving with full head lights, black or white turn it on face the new

religion, everybody’s sitting round watching television, London’s

burning with boredom now, London’s burning dial 999, Up and down

the Westway, in and out the lights, what a great traffic system, it’s

so bright, I can’t think of a better way to spend the night than

speeding around underneath the yellow lights...’ The Clash ‘London’s

Burning’

The Westway to the world story of the Clash can be traced back to 1973

when Mick Jones, and his gran, moved to a flat on the 18th floor of

Wilmcote House, on the Harrow Road Warwick Estate, overlooking the flyover

north of Royal Oak. When Mick was forming his first group up in Wilmcote

House, across the ‘scrapyard vistas of collapsing Victorian housing

stock and corrugated iron’ of proto-punk London, Joe Strummer

called on his former busking partner Tymon Dogg, at 23 Chippenham Road.

Duly housed by the Maida Hill Squatters and Tenants Association at 101

Walterton Road, Joe (when known as John ‘Woody’ Mellor)

was inspired by a local Irish folk band, and Dr Feelgood at the Windsor

Castle, to organise his house mates into El Huaso and the 101 All Stars.

With most of their instruments acquired from Portobello market, the

original line-up was Joe/Woody – guitar, Simon ‘Big John’

Cassell – alto-sax/vocals, Patrick Nother – bass, Antonio

Narvaez/Richard ‘Snakehips Dudanski’ Nother – drums,

and the Chilean exile pop star Alvaro Pena-Rojas – tenor sax.

After playing benefits for victims of Pinochet, and the Royalty cinema

on Lancaster Road, they abbreviated to the 101ers during their shebeen-style

gigs at the Chippenham pub (on the junction of Chippenham, Malvern,

Shirland and Walterton Roads). This 16 week residency became known as

the ‘Charlie Pigdog Club’, in honour of the 101 Walterton

Road dog, equipment was transported to the pub by pram, and the audience

mostly consisted of fellow squatters. Mole (real name: Marwood Chesterton)

became the bassist after meeting Simon Cassell on Ladbroke Grove, Jules

Yewdall (who compiled the 101ers book and Strummer exhibition) took

over lead vocals, and Clive ‘Evil C’ Timperley (later of

the Passions) was recruited on lead guitar. Woody Mellor became Joe

Strummer, as he began his transformation from Woody Guthrie to Bruce

Springsteen wannabe.

The 101ers’ Chippenham residency came to an end in 1975, amidst

reports of an Irish v gypsy barroom battle, shortly before their eviction

from the Big Brother house. Their next squat, 36 St Luke’s Road

(parallel with All Saints Road), was described in Heathcote Williams’

Ruff Tuff Cream Puff squatting estate agents mag as: ‘empty 2

years/entry through rear/no roof/suit astronomer’. Their next

musical residency, in the Elgin at 96 Ladbroke Grove, put them and Notting

Hill on the pub rock map. Here, between May ’75 and January ’76,

the 101ers transformed from a Van Morrison-style ‘urban rhythm’n’blues

orchestra’ into a more streamlined rock’n’roll outfit.

Thus bringing them on-line with the pub rock boom headed by Dr Feelgood,

Ian Dury’s Kilburn and the High Roads, Graham Parker and the Rumour,

and Eddie and the Hot Rods. Joe Strummer’s first original number,

the single ‘Keys to Your Heart’, and the Clash tracks ‘Junco

Partner’ and ‘Jail Guitar Doors’ date back to the

Elgin. As the previously trad Irish folk venue became part of the pub

rock circuit it also featured gigs by the Derelicts, McSmith with Alex

Harvey, and alternative comedy turns by Alexei Sayle, Keith and Tony

Allen. The Chippenham and Elgin pub rock scene was trailblazed by the

Derelicts, another pre-punk group who merged with the 101ers, and went

on to be the Atoms – with Keith Allen, and prag VEC. In ’76

the Derelicts and the 101ers played a benefit for the unsuccessful campaign

to save The Point café on Tavistock Road, featuring ‘Portobello’

and ‘Westway’ songs. The former apparently consisted of

the proto-punk chant: ‘Portobello Road! Portobello Road! W10!’

As the 101ers became the main contenders to Dr Feelgood’s pub

rock bar stool, they went on the road in an old hearse to play the Stonehenge

and Windsor free festivals, squatters benefits and student unions. Locally

they also played the first gig at Acklam Hall under the Westway (on

the site of Neighbourhood); a benefit for the North Kensington Law Centre;

the Harrow Road Windsor Castle, the Western Counties on Praed Street,

Hammersmith Clarendon, Acklam Hall again and the Campden Hill Queen

Elizabeth college. Their last residency was at the Nashville Rooms in

West Kensington, with Ted Carroll’s Rock On Disco and the Sex

Pistols. The first punk rock site in North Kensington is 93 Golborne

Road. Here, in what is now the Moroccan casbah, from the early 70s the

Rock On record stall, of Thin Lizzy’s manager Ted Carroll, boasted

a ‘huge and rocking selection’ of rare/imported rock’n’roll,

rhythm’n’blues, rockabilly, 60s beat, northern soul, US

punk and garage. According to Jon Savage, in his punk rock book ‘England’s

Dreaming’, ‘going there was in itself an act of faith. Golborne

Road was at the wrong end of Portobello Road, 10 years before urban

regeneration.’ Roger Armstrong, the other Rock On owner (now of

Ace Records) recalls “a small space at the end of a kind of enclosed

alleyway… famous for the Elvis wallpaper… from around 1972.”

Joe’s alter-ego ‘Albert Transom’, the Clash valet,

recalls following the thrift pioneers along Golborne Road, as they haggled

over a Dansette record player for £2, and rummaged through the

30p bargainbins for early Who, Stones, Bo Diddley, Ronnie Hawkins and

the Hawks, ‘all the blues, ska and rock’n’roll nobody

wanted’, Howling Wolf, Woody Guthrie, Clarence Gatemouth Brown,

Leadbelly, Bukka White and Big Youth: ‘They would haunt these

little arcades of leather jackets and toy cars and ancient radios, little

record shacks in the back where a tiny dedicated minority would be packed

in leafing through the racks like zombies, all vibrating to Hank Mizel,

all quiffs and petticoat skirts and lumberjack shirts and leather jackets.

Pictures of Gene Vincent and Bill Haley, the odd pair of pointy toed

Cuban heel Chelsea boots…’ The 101ers’ ‘Elgin

Avenue Breakdown’ album came out in the early 80s on their own

Andalucia label, featuring the West Indian ‘metal man’ street

character on the cover, as the Elgin pub was revived as a rock venue.

In this period there were gigs by the Vincent Units (the post-punk 101ers

who included Dudanski and Mole), the Passions (including Timperley),

Nik Turner (from Hawkwind)’s Inner City Unit, Mark Perry’s

Good Missionaries, Scritti Politti, the Androids of Mu and Splodgenessabounds.

In punk psychogeography, if not in reality, the Clash formed in Portobello

market when Mick, Paul and Glen Matlock of the Pistols bumped into Joe

and told him they didn’t like the 101ers but thought he had potential.

As recounted by Joe on the second Clash album ‘Give ’Em

Enough Rope’, in the Mott the Hoople homage ‘All The Young

Punks’: ‘I was hanging about down the market street when

I met some passing yobbos and we did chance to speak.’ In other

versions the pivotal meeting took place on Ladbroke Grove/Road, Westbourne

Grove, Golborne Road, in Shepherd’s Bush, the Lisson Grove dole

office, or it was a total fabrication to cover up the premeditated poaching

of Strummer. By then Matlock, the only hereditary punk local, had accepted

the proto-Clash as ‘4 square Portobello Road boys’. In Pat

Gilbert’s ‘Passion is a Fashion’, Paul recalls Joe

and Mick being laughed at by rudeboys on Golborne Road, for their excesses

with his paint-splattered Jackson Pollock look.

After the Clash first practised in Shepherd’s Bush, at the future

Slit Viv Albertine’s squat, 22 Davis Road, Bernie Rhodes installed

them in their ‘Rehearsal Rehearsals’ studio in Camden, but

the centre of the group’s universe remained Ladbroke Grove. In

the summer of ’76 the last 101ers residence, 42 Orsett Terrace,

near Royal Oak, became the most celebrated/notorious punk squat when

Joe and Palmolive were joined by Paul, Sid Vicious and Keith Levene

(then of the Clash, later Public Image Limited). As living conditions

at Orsett Terrace, in the record hot summer, inspired the early Clash

number ‘How Can I Understand the Flies?’, ‘Albert

Transom’ recalled a visit: ‘They led me down a steep stone

stairway into the basement of an old Victorian ruin in west London.

If there were 50 flies in there, there were a hundred, they walked across

the room stooping to avoid the dense cloud... It was disgusting. I left

before they could offer me some of the filth they were cooking up, some

of which I had seen them picking up out of the road after the veg market

closed up. When one of the marketers saw the lads sifting the rubbish

they deliberately stamped on any whole fruits that they were leaving

behind... I remember the Olympics were on and they had 8 televisions

going because on one the picture worked but the sound didn’t and

vice versa.’

‘Now I’m in the subway looking for the flat, this one leads

to this block this one leads to that, the wind howls through the empty

blocks looking for a home, but I run through the empty stone because

I’m all alone.’ Joe wrote ‘London’s Burning’,

on his return to Orsett Terrace, after watching the traffic from Wilmcote

House. The definitive local Clash anthem is also said to be influenced

by the MC5’s ‘Motor City is Burning’ (about the ’67

Detroit riots), the 1666 Great Fire of London, the Situationist ‘Same

Thing Day After Day’ graffiti under the Westway, JG Ballard and

speed. Joe, in the NME on their ambivalent view of the psychogeography:

“We’d take amphetamines and storm round the bleak streets

where there was nothing to do but watch the traffic lights. That’s

what ‘London’s Burning’ is about.”

After a press preview in their Camden studio, in front of Paul’s

West 10-land mural, the Clash made their proper London debut supporting

the Pistols, at the Screen on the Green in Islington. As the temperature

rose, tempers were lost at what was then seen as an excessive police

presence. After an attempted arrest under the Westway, the inevitable

clash of police and youths came to a soundtrack of Junior Murvin’s

‘Police and Thieves in the streets, scaring the nation with their

guns and ammunition’; echoing the near civil war situation in

Jamaica, and homegrown football hooliganism. ‘Albert Transom’

recalled getting caught up in the first incident under the Westway.

After a group of ‘blue helmets sticking up like a conga line’

went through the crowd, one was hit by a can, immediately followed by

a hail of cans: ‘The crowd drew back suddenly and the Notting

Hill riot of 1976 was sparked. We were thrown back, women and children

too, against a fence which sagged back dangerously over a drop. I can

clearly see Bernie Rhodes, even now, frozen at the centre of a massive

painting by Rabelais or Michelangelo… as around him a full riot

breaks out and 200 screaming people running in every direction. The

screaming started it all. Those fat black ladies started screaming the

minute it broke out, soon there was fighting 10 blocks in every direction.’

As the police charged up Westbourne Park Road Joe found sanctuary in

the Elgin, then he and Paul joined in the traffic cone and occasional

brick throwing action, but they ended up in a shot by both sides situation.

On Janet Street-Porter’s London Weekend Show Joe said: “We

got searched by policemen looking for bricks, and later on we got searched

by Rasta looking for pound notes in our pockets.”

That night, Joe, Paul and Sid were warned off by a black woman when

they tried to enter the Metro youth club on Tavistock Road. As Joe told

Tony Parsons: “It wasn’t our riot, though we felt like one.”

Inspired by black anarchy in the UK, as much as by the Sex Pistols,

Joe wrote the lyrics of the first Clash single: ‘White riot, I

wanna riot, white riot, a riot of my own, black man gotta lot of problems

but they don’t mind throwing a brick, white people go to school

where they teach you how to be thick, and everybody’s doing just

what they’re told to, and nobody wants to go to jail.’ Quite

clearly meaning that he felt excluded from the black riot, but, at the

same time, empathy with the cause. Nevertheless, the song was misinterpreted

as a call for whites to riot against blacks ’58 style, by a students

union. On the whole, white hooligan youth got the intended meaning.

‘White Riot’ is also said to be influenced by the Weathermen

US hippy terrorist group’s ‘Revolutionary Songbook’,

via Bernie, but as Joe explained his consumer society critique to the

NME: “The only thing we’re saying about blacks is that they’ve

got their problems and they’re prepared to deal with them, but

white men, they just ain’t… they’ve got stereos, drugs,

hi-fis, cars.”

Within the ‘Sandinista’ triple set, on the ‘One More

Time (In The Ghetto)’/‘Hitsville UK’ local album,

they return to Ladbroke Grove with the 101ers’ ‘Junco Partner’

from the Elgin, ‘The Leader’ (referring to Profumo according

to Nick Kent), ‘The Crooked Beat’ (police), ‘Lightning

Strikes’, ‘Up in Heaven’ (towerblocks), ‘Corner

Soul’ (blues), ‘Let’s Go Crazy’, ‘Police

On My Back’, ‘The Street Parade’ (Carnival). ‘Corner

Soul’ captures the pre-Carnival tension, as the forces of Notting

Hill Babylon put the area under heavy manners, ‘searching every

place on the Grove’, asking: ‘Is the music calling for a

river of blood? Beat the drums tonight, Alphonso, spread the news all

over the Grove… total war must burn on the Grove… Spread

the word tonight please Sammy, they’re searching every house on

the Grove, don’t go alone now Sammy, the wind has blown away the

corner soul.’ ‘Let’s Go Crazy’ encapsulates

the militant reggae mas and mayhem, featuring steel drums and namechecks

Jah Shaka, sticksmen and ganja, ‘bricks and bottles, corrugated

iron, shields and helmets, Carnival time!… young men know when

the sun has set darkness comes to settle a debt… with indiscriminate

use of the power of arrest, they’re waiting for the sun to set,

You wanna go crazy, then let’s go crazy…’ Then Joe

‘disappears/joins/fades’ into the steel pan dub of ‘The

Street Parade’.

In the early 80s the Clash posed on Freston Road, in front of the squatted

Apocalypse Hotel (the old Trafalgar pub, on the site of the ‘Frestonia’

Chrysalis office building), Mick already with a hip-hop ghettoblaster.

For the rest of the 80s Futura2000 graffiti marked the spot of the punky

hip-hop party. Futura was the Clash rapper on ‘Overpowered by

Funk’ on ‘Combat Rock’, and their on-stage graffiti

artist.

When Joe went AWOL on ‘Combat Rock’ duty, at the time of

the Falklands war, music press briefings were held in Mike’s Café

on Blenheim Crescent. After the protracted break-up of the Clash Joe

was arrested for drink driving round the corner on Kensington Park Road.

He later paid homage to Portobello with ‘Shouting Street’,

on his 1990 Latino Rockabilly War album ‘Earthquake Weather’.

Joe legally occupied a property on Lancaster Road. As well as the Lonsdale

and the Elgin, most local pubs have some Clash connection. Joe cited

the Portobello Star as his favourite, and the Warwick/Castle as his

least favourite after being barred in the 90s.

The Strummer/Jones songwriting partnership resumed on the second BAD

album, ‘Number 10 Upping Street’, after Mick produced Joe’s

‘Sid and Nancy: Love Kills’ track. In 1983 Mick and Paul

starred in Joe’s gangster home-movie ‘Hell W10’, as

the gangster boss and ‘The Harder They Come’ rebel respectively,

in scenes on Portobello, a fight outside the Electric cinema, and beside

the Westway, another fight outside the Tavistock Crescent Frog &

Firkin (now the Mother Black Cap). Joe appeared in Alex Cox’s

‘Sid and Nancy’ follow-up, the punk western ‘Straight

to Hell’, Jim Jarmusch’s ‘Mystery Train’, and

Cox’s ‘Walker’. After his death in 2002 local tributes

were paid under the Westway at Westbourne Studios, on Ladbroke Grove

in the Elgin, and by the surviving 101ers at the Tabernacle in Powis

Square. Joe’s final local gig at Kensal Green was attended by

the first Clash critic Charles Shaar Murray, the last Clash groupie

Courtney Love, and a group of firemen – after his last London

gig was a firemen’s strike benefit in Acton. ‘Strummerville’

was founded at Glastonbury, and filmed under the Westway roundabout,

in Stable Way, by Julien Temple. In one of his last interviews Joe said:

“There’s a brick wall in Notting Hill near Portobello market

that I would rather look at for hours than go to Madame Tussaud’s

and it’s totally free and full of history.”