PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL 2006

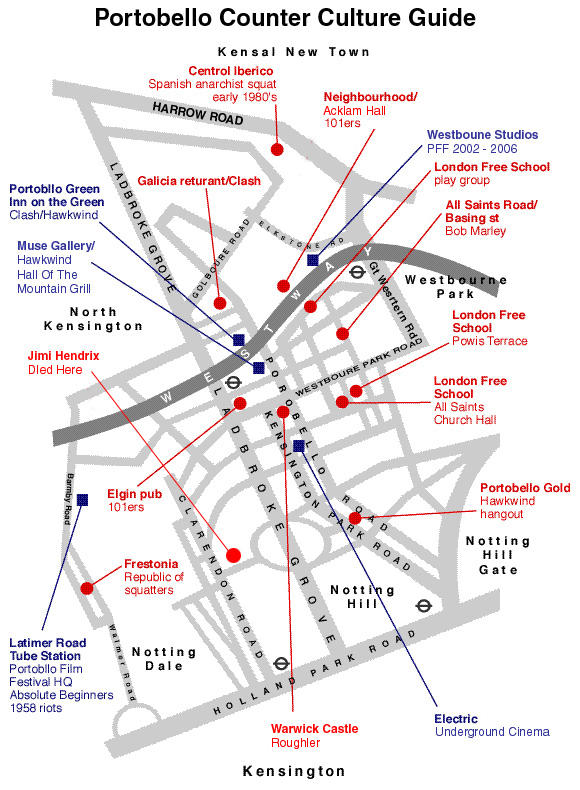

Counter Culture Portobello

Psychogeographical History

by Tom Vague.

Back to main

page

Part 1 - ABSOLUTE

BEGINNERS

Part 2 - THE LONDON FREE SCHOOL

Part 4 - BOB MARLEY AND THE WAILERS

Part 5 - STRUMMERVILLE

Part 6 - FRESTONIA

Part 7 - SKETCHES OF SPAIN

3 HAWKWIND

“It’s not the speed, Jimi,” said Shakey Mo, “it’s

the H you got to look out for.” Jimi was amused. “Well,

it never did me much good.” “It didn’t do you no harm

in the long run,” Shakey Mo laughed. He could hardly hold on to

the steering wheel. The big Mercedes camper took another badly lit bend.

It was raining hard against the windscreen. He switched on the lamps.

With his left hand he fumbled a cartridge from the case on the floor

beside him and slotted it into the stereo. The heavy, driving drumming

and moody synthesizers of Hawkwind’s latest album made Mo feel

much better. “That’s the stuff for energy,” said Mo.

Jimi leaned back. Relaxed, he nodded…’ Michael Moorcock

‘A Dead Singer’ 1974

The main event of the first late August Carnival weekend of the 70s

was a space-rock skinhead moonstomp on Wormwood Scrubs. After initial

fears of aggro, rain and accompanying technical problems (ie. electrocution)

held up proceedings, Hawkwind won over the local skinheads, as much

as the Kensington Post reporter who applauded the ‘brilliant young

men from Notting Hill’, for eschewing commercialism in favour

of doing ‘their own proverbial multi-echo booming explosive thing.’

The QPR bovverboys contented themselves with mimicking the gyrating

hippy dance, and the promoters (from the Lancaster Road Crypt folk club)

sensibly replaced Quintessence with the more down to earth Quiver (who

would come up with Rod Stewart’s 1975 hit ‘Sailing’).

After Wormstock, as the West London Observer named the event, Hawkwind

became the Ladbroke Grove band of the rest of the hippy era.

The Dutch music paper ‘Ear’ cited the founder Dave Brock

for capturing ‘the wind-blown and semi-estranged character of

Ladbroke Grove and probably as a result, Hawkwind quickly grew from

an idea to reality.’ But, back in ’70, Mick Farren thought

of them as ‘just up from the country’, and they would spend

more time playing festivals than in town. Hawkwind came into existence

as Group X at All Saints church hall in 1969, then became Hawkwind (at

first Hawkwind Zoo) under the management of Doug Smith’s Clearwater

Productions, whose office was on Great Western Road. The name is said

to come from a nickname acquired by the singer-saxophonist Nik Turner,

on account of his ability to synchronize bodily functions, rather than

from a Tolkien character as you might have expected. On their 1971 album

‘X In Search of Space’ cadets were invited to ‘thrill

to the android replicas, share the cruel sounds of limitless space,

co-pilots of spaceship Earth, experts in astral travel, switch all channels

through to the void, fill your heads with peace and fire your flesh

rockets with the liquid fuel of love, and let us ride together on orgasmic

engines to the stars. Beware if you fly Hawkwind, there ain’t

no return.’

‘Mo shuffled slowly up Lancaster Road and turned the corner into

Portobello Road. He thought he saw the black and chrome Merc cross the

top of the street. The buildings were all crowding in on him. He saw

them grinning at him, leering. He heard them talking about him. There

were fuzz everywhere. A woman threw something at him. He kept going

until he reached the Mountain Grill and had stumbled through the door.

The cafe was crowded with freaks... Dave looked up, grinning pensively.

“Hi, Mo. When did you get back to town?” He was dressed

in new, clean denims with fresh patches on them. One of the patches

said ‘Star Rider’. “Just got in.”… Dave

counted 50 Mandies into an aspirin bottle. Mo reached into his jeans

and found some money. He gave Dave a £5 note and Dave gave him

the bottle. Mo opened the bottle and took out a lot of the pills, swallowing

them fast. They didn’t act right away, but he felt better for

taking them. He got up. “See you later, Dave.” “See

you later, man,” said Dave. “Maybe in Finch’s tonight.”

“Yeah.”

‘And in the Grove, by Gate and Hill, midst merry throng and market

clatter – stood the Hall of the Mountain Grill where table strain’d

‘neath loaded platter (from the Legend of Beenzon Toste).’

As the Pink Fairies did the ‘Portobello Shuffle’ into Pinkwind

under the Westway, we enter the time of the Hawklords. In 1974 Hawkwind’s

fifth album, ‘The Hall of the Mountain Grill’, was named

in honour of the legendary greasy spoon cafe at 275 Portobello Road

(the last house before the tubeline and the Westway, until recently

George’s Famous Mountain Grill); and also as a spoof of King Crimson’s

‘In the Court of the Crimson King’ Island album. In ‘Pete

Frame’s Rock Family Trees’ the Hawkwind singer/sci-fi writer

Bob Calvert, aka ‘Captain Lockheed’ (who wrote ‘Silver

Machine’), described it as “a working man’s cafe in

Portobello Road, frequented by all the dross and dregs of humanity.

Dave Brock always used to go there and eat, which is how I first came

to meet him – because I used to eat there too when I worked on

Frendz magazine. It was a kind of left bank café-meeting place

for the Notting Hill longhairs, a true artists’ hangout, but it

never became chic, even though Marc Bolan, David Bowie and people like

that often went there.”

30 years on, it still hadn’t, even though everywhere else on Portobello

had, and it seemed that any pop appeal the premises once possessed had

long since gone with the Wind. Then Mike Skinner/The Streets posed there

with a fry up for some west London chav street cred in an ‘Observer’

photo shoot. Overnight the rock landmark greasy spoon was gentrified

into a trendy restaurant/takeaway; at first ‘No Longer The Greasy

Spoon’, now Babes’n’Burgers. The quest of the holy

Mountain Grill was lost, and the time of the Hawklords finally came

to an end.

The apocalyptic crashed spaceship sleeve of the ‘Mountain Grill’

album was by Barney Bubbles, along with Hawkwind’s generic heavy

metal/gothic rock logo, the atmospheric inner-sleeve café photo

was by Philm Freax/Phil Franks. The ‘Hall of the Mountain Grill’

track is a remarkably un-cosmic instrumental, before the proto-punk

Lemmy/Farren number ‘Lost Johnny’. In this mid-70s strata

of acid-rock geology the ‘Psychedelic Warlords’ of the Wind

numbered Dave ‘Baron’ Brock, Nik Turner, aka ‘the

Thunder Rider’, and Lemmy ‘Count Motörhead’.

The former Hendrix roadie, Rockin’ Vickers, Motown Set, Sam Gopal’s

Dream and Opal Butterfly guitarist, Ian ‘Lemmy’ Kilminster

(sometimes Kilmister), was quoted as saying: “Hawkwind fits exactly

into my philosophy. They’re weird – that suits me.”

But, after their 6th album ‘Warriors on the Edge of Time’,

and the ‘Kings of Speed’/‘Motörhead’ single,

he was sacked; for the occupational hazard of being busted with speed

at Canadian customs; regarded by many as the biggest mistake in rock

history. The mid 70s line-up also included Stacia, the equally notorious

Hawkwind dancer, who was summed up by Calvert in another Mountain anecdote;

in which an awestruck ‘spade cat’ repeats “Nice lady”.

In the sci-fantasy novel ‘The Time of the Hawklords’, by

Michaels Moorcock and Butterworth, their post-apocalypse HQ was ‘the

yellow van commune’ at 271 (now the Portobello Hot Food takeaway):

‘adjacent to the burnt-out shell of the legendary Mountain Grill

restaurant – the supplier of good, plentiful food to many a starving

freak who roamed the inhuman streets of the period.’ The previous

tenants, who painted the building in geometric hippy designs, were ‘outlaw

publishers of underground pamphlets, friends of Hawkwind who had been

hideously killed by marauding gangs of puritan vigilantes.’ In

the later 70s 271 (which still has a large hippy style number) was occupied

by the post-pub punk group Warsaw Pact; as well as featuring Lucas Fox,

the original Motörhead drummer, they are notable for causing the

Manchester band Warsaw’s namechange to Joy Division. In the Hawklords

book the post-apocalypse kids gather outside to remind Hawkwind to play

for their sonic healing. Whereas, in rock real-time, when the book came

out in 1976 the kids were telling them to stop. Nevertheless, Hawkwind

carry on prog rocking regardless into our own time. As they held space

rituals at Stonehenge, like rock morlocks in HG Wells’ timemachine,

they took punk and acidhouse on board. In 2005 they reappeared under

the Westway, in a prog rock time warp at the Inn on the Green.

In his 1974 shortstory ‘A Dead Singer’, in ‘Moorcock’s

Book of Martyrs’, Hendrix is resurrected, or his ghost haunts

the street hippies of the Grove. ‘Shakey Mo’, the Deep Fix

roadie from his Jerry Cornelius time travel novels, had spent too long

in Finch’s, suffering from severe acid-rock withdrawal symptoms,

and become Hendrix’s roadie on the astral plane. On a final Grove

stop-off he visits the Mountain Grill cafe on Portobello, scores Mandies

on Lancaster Road, and gets into a fight in Finch’s, before his

last gig DJing an astral-rock session in an Oxford Gardens basement.

“Hi,” said the newcomer. “I’m looking for Shakey

Mo. We ought to be going.” The black man stepped across the others

and knelt beside Mo, feeling his heart, taking his pulse. The chick

stared stupidly at him. “Is he alright?” “He’s

ODed,” the newcomer said quietly, “he’s gone, d’you

want to get a doctor or something, honey?” “Oh, Jesus,”

she said. The black man got up and walked to the door. “Hey,”

she said, “you look just like Jimi Hendrix, you know that?”

“Sure.” “You can’t be – you’re not

are you? I mean, Jimi’s dead.” Jimi shook his head and smiled

his old smile. “Shit, lady. They can’t kill Jimi.”

He laughed as he left.’ In Moorcock’s ‘Great Rock’n’Roll

Swindle’ novel Jimi, Marc Bolan and Sid Vicious follow events

from the celestial ‘Cafe Hendrix’. As well as his space-rock

novels featuring Hawkwind, Hendrix and the Sex Pistols, Moorcock wrote

‘Kings of Speed’, various other Hawkwind and Blue Oyster

Cult numbers, and played guitar on Bob Calvert’s solo albums.

In the 70s he lived on Colville Terrace, and mentions Annie Lennox in

‘King of the City’, working at Mr Christian’s deli

on Elgin Crescent – before the Tourists arrived.

In the early 70s the Mountain Grill acted as the backstage for the hippy

free gigs under the Westway flyover. After the earliest ‘Fun and

Games’ and ‘Grove Rock’ sessions, in 1973 the Westway

Theatre hosted ‘Magic Roundabout’ gigs presented by Greasy

Truckers Promotions, featuring Ace, Kevin Ayers (of Soft Machine, who

ran off with Branson’s first wife), Burlesque, Camel, Chilli Willi,

Keith Christmas, Henry Cow, Clancy (who later included Barry Ford of

later still reggae renown with Merger, and Gaspar Lawal), Fat City,

the Global Village Trucking Company, Gong, Skin Alley, Sniff and the

Tears, and Spyra Gyra. In the bays to the east (where Acklam Hall/Neighbourhood

and the Playstation skatepark would later appear) Hawkwind went ‘In

Search of Space’, as pictured on the fold-out sleeve of their

’71 album, and merged with the Fairies for Pinkwind gigs. Moorcock’s

factional memoir ‘King of the City’ features a Saturday

afternoon free gig under the Westway, by Brinsley Schwarz with Nick

Lowe. His ‘Dennis Dover’ character reaches amphetamine rock

nirvana with his Basing Street session musician group, playing to an

audience of ‘Swedish flower children, American Yippies’

and ‘French ’ippies’.

On Lemmy’s dismissal from Hawkwind, he promptly formed Motörhead,

originally with Larry Wallis of the Pink Fairies and Lucas Fox (later

of Warsaw Pact). In the Face David Toop described Hawkwind and the Fairies

as ‘Britain’s own versions of the MC5, most of them grouped

around the commune life of London’s Ladbroke Grove and Notting

Hill. Drugs, politics, sex. It was the hardcore section of Britain’s

response to Haight Ashbury. Motörhead, rock’n’roll

cowboys, the ‘bring on the virgins’ warriors, carry some

of that legacy with them in their mixed-up libertarian politics.’

After their regular Hammersmith Odeon gigs, Lemmy occasionally slept

in St Luke’s Mews, off All Saints Road, where his neighbours included

Joan Armatrading, Chet Baker, Richie Havens and Marsha Hunt. His local

roadcrew featured Mikkelson, the legendary black All Saints hells angel,

while another local biker was known as Goat. But mostly, when off the

road, Lemmy could be found on the fruit machine of the Princess Alexandra

pub, at 95 Portobello Road. More commonly renowned as the Alex, the

bikers and National Front pub-cum-speed dispensary, this was originally

a locals’ local, founded as a rock venue by Mick Farren, Boss

Goodman, Lemmy and Steve Peregrin Took in the early 70s, that was also

resorted to by Hawkwind, the Fairies, Pistols, Clash, Damned, Ramones

and Stray Cats. After some pool hall aggro, in which Lemmy sided with

a non-Aryan, the Alex became the first Notting Hill pub to be gentrified

– back in the mid 80s – into the Portobello Gold American

style bar-restaurant.

The bikers briefly rallied in the Colville Hotel, at 186 Portobello

(also swiftly gentrified into the Ground/First Floor bar/restaurant),

when Lemmy was residing in Colville Houses, up Talbot Road. George Butler

recalls the bikers’ tarantula phase here, in which biker girls

were sent screaming out into the market. Lemmy wrote the Motörhead

track ‘Metropolis’ after seeing the film at the Electric,

and Motörhead T-shirts, recently enjoying a fashionista revival,

have to be the most successful Portobello pop product. The Narrow Boat

in Kensal was another shortlived 80s biker pub, and in the late 80s

Motörhead were on the GWR label. In the 90s they were represented

by the Girlschool roadie-turned-Warwick barmaid, Tank, who’s currently

at the Western Arms on Kensal Road.

After appearing in ‘Beachboys in London’ in ’66, the

Alex acquired the less hip distinction of being in Status Quo’s

‘Rockin’ All Over The World’ video in ’77. George

Butler (of the Lightning Raiders) recalls inadvertently being in it,

when he left the pub as they went through the antiques market, pretending

to play on the back of a truck. And this isn’t just a tenuous

headbanging connection as the Quo frontman Francis Rossi was another

local. In 2000 Dave ‘Boss’ Goodman, the Deviants/Fairies

tour manager and underground food correspondent, was back in the Gold

working as the chef when, following in the footsteps of Beachboys, Ramones

and Stray Cats, the notorious American saxophonist Bill Clinton made

a celebrated appearance. The Earl of Lonsdale, at 277-81 Westbourne

Grove, continued rocking through the 60s as Henekey’s, in spite

of some bad reviews. Mick Farren described it, as ‘the prime freak

pub of the time’, becoming too much of a tourist and police attraction,

before the pub’s ‘biggest drugs bust in history’.

In an early 70s Frendz review Finch’s was ‘where your cooler,

more nervous, refined or trendy dealer goes to relax over a jar or two

of plump barmaid.’ Nick Kent recalled the New York Dolls guitarist

Sylvain Sylvain ‘in Finch’s back in good old Ladbroke Grove

dealing dope.’ Julie Christie, Keith Moon, John Bindon from ‘Performance’,

the Windsor chapter hells angels, Malcolm McLaren and Hanif Kureishi

have also been cited as Finch’s locals. In the mid 70s it was

described as the most evil pub in England in a tabloid shock-horror

drugs expose, Moorcock’s ‘King of the City’ pub drugs

guide has: ‘Speed in the Alex. Dope in the Blenheim (on the site

of E&O). Junk in Finch’s. They kept tarting up Finch’s

and Henekey’s and we kept tarting them down again. As my friend

DikMik (Hawkwind’s oscillator operator) put it late one evening;

you could take the needles out of the toilets but you couldn’t

take the toilets out of the needles.’

The Duke of Wellington, at 179 Portobello Road (on the north corner

of Elgin Crescent), was the Portobello flagship of the Finch’s

bar chain, which included branches at Notting Hill Gate (the old Hoop),

in Fulham, and Soho. The Lonsdale was another earlier in the 20th century,

and the Goodge Street one featured in Donovan’s ‘Sunny Goodge

Street’. In its Finch’s heyday, the anti-Napoleon of Notting

Hill bar was reviewed more favourably, in the ‘Alternative London’

guidebook, as ‘one of the liveliest pubs – rough enough

to keep out Americans. You can play, sing or anything else provided

you don’t need room to move.’ According to an early 80s

Time Out pub guide it was ‘a true ethnic pub, where Guinness is

drunk and anything could happen.’ Today the heavy rock influence

lingers on in the Café Progreso opposite, and the Gong shop up

the road.

‘Since his comeback (or resurrection as Mo privately called it)

Jimi hadn’t touched a guitar… he was taking a long time

to recover from what happened to him in Ladbroke Grove… In Finch’s

on the corner of Portobello Road he’d wanted to tell his old mates

about Jimi, but Jimi had said to keep quiet about it, so when people

had asked him what he was doing, where he was living these days, he’d

had to give vague answers… “All that low energy shit creeping

in everywhere, things are bad.” Jimi had changed the subject,

making a jump Mo couldn’t follow. “People all over the Grove

playing nothing but fake 50s crap, Simon and Garfunkel. Jesus Christ!

Was it ever worth doing?” Michael Moorcock ‘A Dead Singer’

1974