PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL 2006

Counter Culture Portobello

Psychogeographical History

by Tom Vague.

Back to main

page

Part 1 - ABSOLUTE

BEGINNERS

Part 3 - HAWKWIND

Part 4 - BOB MARLEY AND THE WAILERS

Part 5 - STRUMMERVILLE

Part 6 - FRESTONIA

Part 7 - SKETCHES OF SPAIN

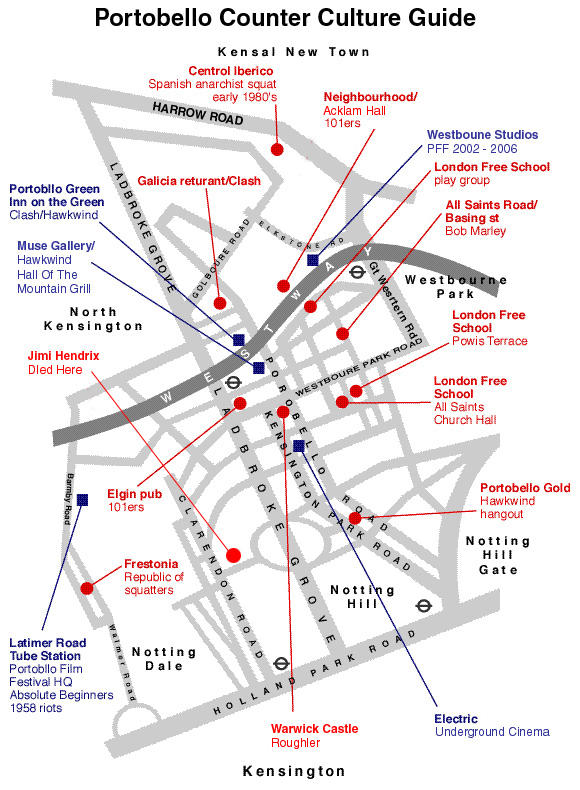

2 THE LONDON FREE SCHOOL

After the 1965 Albert Hall beat poetry happening, the next key event

in the history of British counter-culture was the London Free School.

This proto-community action group has been described as an ‘anarchic

temporary coalition’ of post-Rachman housing activists and the

new hippy generation. To varying degrees of involvement, the latter

numbered John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, Michael X, Pete Jenner, Michael

Horovitz, Graham Keen, Neil Oram, Jeff Nuttall, Mike McInnerney, John

Michell, Julie Felix, Joe Boyd of Electra Records, the jazz writer Ron

Atkins, the Warhol star Kate Heliczer, Harvey Matusow, the Beatles manager

Brian Epstein and RD Laing. At the inaugural meeting on Elgin Avenue

the group announced that ‘the Free School hoped to run some local

dances, carnivals in the summer, playgroups for children, street theatre,

and so on.’

Hoppy told me it was “an idea – it lasted for a few months

and so many interesting things came out of it… it was one of the

myriad things that went down in those days.” In ‘Days in

the Life’ he called it “a scam”, and “an idea

that really shouldn’t be inflated with too much content, because

there really wasn’t too much content.” His main co-hort,

Pete Jenner, the LSE economics lecturer-turned rock group manager, described

the Free School as either the first “public manifestation of the

underground in England”, or hippy dogooding that amounted to little

more than “a couple of sessions in some terribly seamy rooming

house of Michael X’s.”

But it started Notting Hill Carnival; at any rate, as explained by Jeff

Nuttall in ‘Bomb Culture’: ‘Ultimately the Free School

did nothing but put out a local underground newsletter and organise

the 2 Notting Hill Gate Festivals, which were, admittedly, models of

exactly how the arts should operate – festive, friendly, audacious,

a little mad and all taking place on demolition sites, in the streets,

and in a magnificently institutional church hall.’ In the actual

Free School building, 26 Powis Terrace/Hedgegate Court (a former brothel

opposite David Hockney’s studio), by all accounts not much happened

apart from band practices in Dave Tomlin’s psychedelic basement.

Michael X, posing Puff Daddy-style with a silver-topped cane, is said

to have scared off any actual local people.

At the same time, the Free School received its first and best publicity

through Michael, when on May 15 1966 Rhaune Laslett’s neighbourhood

playgroup, at 34 Tavistock Crescent (since demolished), was visited

by Muhammad Ali. In the run up to his second Henry Cooper fight at Highbury,

Ali (when still widely known as Cassius Clay) appeared apparently dressed

for the occasion in a Beatles-style suit. In ‘The Grove’

newsletter he was reported sitting on the floor talking to the kids,

as the street became blocked by onlookers: ‘The crowd went wild

and he just grinned. “Are you happy?” a voice shouted. “Yes,

I’m happy here”, he replied.’ After visiting other

houses in the area, Ali inevitably ended up at Frank Crichlow’s

El Rio café on Westbourne Park Road. There Michael attempted

to take over proceedings, and serve only halal food to impress the Nation

of Islam, causing a pre-big fight bout between himself and Frank. By

all accounts Michael’s conversion to Islam was as genuine as his

political commitment. After Ali retained the title Michael paraded his

shorts, splattered with Henry Cooper’s blood, around Notting Hill.

By ’66 Michael’s press profile had gone from ‘landlord

unable to live with himself’ to ‘the authentic voice of

black bitterness’, as he was touted as the leader of the British

Black Power movement. In spite of pressure from the police and Council

on the Free School to drop him from the group, Michael stayed and the

first Carnival happened, in late September, at Michaelmas (one of the

medieval quarter days when, appropriately enough, rents were due to

landlords). In ‘Notting Hill in the 60s’ his Carnival king

status was thus verified: “He was a visionary right, all this

Carnival down in the Grove is down to Michael you know… those

guys decided to come on the road one day and they come up out and they

following he and the next thing he’s talking to this woman who’s

running a neighbourhood thing down on Tavistock Road, Rhaune Laslett,

and they twos up and that kick off from there.”

As far as any kind of evidence goes, in 1964 and ’65, the alternate

years of the media myth first Carnival, nothing happened. Rhaune Laslett

told Time Out that the idea came to her in a vision, after she had been

dealing with a tenant-landlord dispute, “that we should take to

the streets in song and dance, to ventilate all the pent-up frustrations

born out of the slum conditions.” Another social worker, John

Livingstone, wrote to the Independent to dispel the myth that the Carnival

began in ’68 ‘in response to racial unrest’: ‘The

odd thing was that, while we discussed every local social problem under

the sun, race was in itself not one of them.’ According to him,

Rhaune started the Carnival for the local kids, who couldn’t afford

to go on holiday, but instead got to meet Mohammad Ali, and see the

World Cup in English hands – on the other great ’66 parade

along Ladbroke Grove.

The 1966 Notting Hill Fayre & Pageant, or the London Free School

Fair, was a weeklong series of events following the traditional English

carnival/fair format, as more accurately portrayed in the ‘Bedknobs

& Broomsticks’ knees-up than by most Carnival historians.

The pageant on Sunday September 18 1966 featured a man dressed as Elizabeth

I and children as Charles Dickens characters, ‘musicals’,

and a Portobello procession; consisting of the London Irish girl pipers,

a New Orleans-style marching band, Ginger Johnson’s Afro-Cuban

band, and Russell Henderson’s Trinidadian steelband (from the

Coleherne in Earl’s Court), followed by a fire engine. The next

Saturday a torchlight procession was planned, and throughout the week

All Saints church hall, on Powis Gardens (on the site of the old peoples’

home hall), had various ‘social nights’. These included

‘international song and dance’, jazz and folk, Dickens amateur

dramatics, and ‘old tyme music hall’. The first Carnival

also featured inter-pub darts. The West London Observer reported ‘such

jollity and gaiety at the Notting Hill Pageant’ that the organisers

‘decided to make the pageant an annual event.’ The radical

70s Carnival chairman Darcus Howe has recalled ‘66, not all that

fondly, with a few hundred people dancing in the rain to one steel band,

led by Andre Shervington dressed in African costume.

Michael Horovitz’s 1966 ‘Carnival’ poem adds to the

Beatles’ local street credibility with: ‘Children –

all ages chorusing – we all live in a yellow submarine –

trumpeting tin bam goodtime stomp – a sun-smiling wide-open steelpan-chromatic

neighbourhood party making love not war.’ In the hippy origin

theory, as propagated by Horovitz in ‘Days in the Life’,

Notting Hill Carnival began as a jazz-poetry extension of the Albert

Hall beatnik happening, and the headline act was Pink Floyd. In what

could be hippy confusion with the renowned Nottingham Goose Fair, Horovitz

remembered saying: “There used to be a goose fair or something,

spelt F-A-Y-R-E, before the last war, and Hoppy said ‘Hey, man,

there used to be this fayre thing! Listen, man, you poets, we ought

to get together and start live ‘New Departures’ (Horovitz’s

poetry mag) in the local community.” The Horovitz first Carnival

recollection goes on (probably merging various mid to late 60s gigs

and demos) to include Pink Floyd and Soft Machine, the first psychedelic

lightshows (by Mark Boyle and Joan Hills), and hippies in pantomime

animal costumes leading local kids into the Powis Square gardens. In

his ‘Vision of Portobello Road’ poem, in the ‘Children

of Albion’ anthology, there are ‘screaming tricycles and

melons, lettuces and ripe negroes, stripe shirt, and others proud walking,

it’s gay and sad and rich enough.’

In a similar vein, Neil Oram’s ‘Raps from the Warp’

play features a hippy guru character addressing his commune in the Free

School basement (at 26 Powis Terrace). In other scenes a hippy talks

about opening Colville Square Gardens, so the kids can generate more

positive cosmic energy, and a psychedelic pied piper/saxophonist leads

Portobello processions of ragged kids. At the time the first issue of

the Free School newsletter, ‘The Gate’, reported that ‘the

photography group (Hoppy and Graham Keen) was last seen at a ‘happening’

at the Marquee club, surrounded by people dancing around in cardboard

boxes. The teenage group have been playing folk music, and listening

to Dylan records.’

As Hoppy became involved in the Marquee’s ‘Spontaneous Underground’

happenings, the London Free School spawned the Electra subsidiary label

DNA, for an album by the surrealist jazz band AMM, who performed in

lab coats. All Saints hall went on to host Dave Tomlin’s ‘Fantasy

workshop’, a proto-ambient house ‘gallery of peace and relaxation’,

and the ‘Sound/Light workshops’ of Pink Floyd. After the

fair, in October and November, Hoppy presented ‘London’s

farthest out group in interstellar overdrive stoned alone astronomy

domini – an astral chant and other numbers from their space-age

book.’ On Powis Gardens the Pink Floyd Sound dropped the ‘Sound’

from their name (the rest of which came from ‘2 old blues guys’),

and the Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley covers from their set, as they developed

their whimsical folk pop further out there into the prog-rock freakouts

‘Interstellar Overdrive’ and ‘Astronomy Domini’.

What turned into a 12 gig residency, encouraged by the liberal vicar,

and promoted by Timothy Leary’s ‘turn on, tune in, drop

out’ slogan, has been described as initially ill-attended, or

elite ‘social nights’, proper educational events with questions

from the audience afterwards, and auditions for EMI. The legendary original

singer Syd Barrett was inspired to write ‘See Emily Play’,

their second single (duly covered by Bowie), in All Saints hall, by

the early Floyd fan Emily Young. Now a renowned local sculptor, she

was then the ‘aristocratic flower child’ who ‘tries

but misunderstands, dressed in a gown that touches the ground.’

The daughter of Wayland Young, Lord Kennet (the author of ‘Eros

Denied’), girlfriend of Dave Tomlin, and some sort of muse spirit

to poor old Syd, Emily was recruited from Holland Park School to the

London Free, by Hoppy, with her schoolfriend Anjelica Huston (the daughter

of the director John, future actress and wife of Jack Nicholson). Holland

Park Comprehensive was almost as prog as the Free School, with Andy

McKay of Roxy Music as a music teacher and muso parents including Alexis

Korner and John Mayall.

The All Saints avant-garde rock scene seems to fall somewhere between

San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom and New York’s Factory,

in most accounts veering towards the west coast sound of the Grateful

Dead. Hoppy says: “There was a certain amount of synchronicity

in that it turned out that what we were doing in London towards the

end of ’66 was also being done in San Francisco, lightshows and

showing movies on walls and generally throwing together different art

forms. The Velvets were in New York, as far as I know they weren’t

quite the same scene, but that was sort of thrown into the mix as well.”

But in Nicholas Schaffner’s ‘Saucerful of Secrets’

Pink Floyd book originally New York was more influential, with the All

Saints gigs imitating Warhol’s Exploding Plastic Inevitable shows,

Hoppy’s Warhol star girlfriend Kate Heliczer bringing over VU

tapes, and Pete Jenner making an attempt to become the Velvets manager.

Emily Young and Anjelica Huston have described themselves at the time

as existentialists or proto-goths, rather than colourful hippies, always

wearing regulation Velvet Underground black clothes and make-up. Jenner

says Pink Floyd were imitating the Grateful Dead, without knowing what

they sounded like, or taking acid, but turned out more psychedelic,

“in the purest psychedelic sense.” At the first All Saints

gig, according to Schaffner, the American associates of Timothy Leary,

Joel and Tony Brown, turn up, tune in and project slides on the group.

Then the British psychedelic ‘blob’ liquid-slide lightshow

was developed by Pete and Sumi Jenner, John Marsh, Joe Gannon, Peter

Wynne-Wilson and ‘the psychedelic debutante’ Susie Gawler-Wright.

The ‘business beatnik’ Pete Jenner gave up his day job at

the LSE to become Pink Floyd’s manager, and set up Blackhill Enterprises,

with Andrew King, Syd, Roger Waters, Rick Wright and Nick Mason, on

Alexander Street, off Westbourne Grove. Jenner was also the first Carnival

treasurer, making Pink Floyd more influential on the event than the

Beatles. A loved up Courtney Tulloch called the London Free School ‘a

prolonged love programme which ended with Carnival and continued in

the form of IT.’ During the ’67 ‘summer of love’

Tulloch wrote of worsening relations between the police and black community

and looked back to the ’66 fair – incorporating the Caribbean

‘Notting Hill Carnival’, and jazz enthusiast police –

as the hippy heaven W11: Michael ‘cooling it by the door, impersonating

a villain but coming over strongly as the saint he is, hugging all the

white guys and talking beautifully about the exciting way everyone was

enjoying their little bit of freedom.’ Hoppy ‘always jumping

about the place in his camouflage kit, flying on and off the weeny stage.’

Paradoxically, Emily Young’s ‘Days in the Life’ recollection

of the Westway site is of a Roger Waters-directed post-apocalypse film

set: “It was the dark side of the moon, the other side of wonderful

Britain. It was the Martian wasteland. There were dead donkeys lying

around, and dead people, a dead baby one time. A very weird place, desolation...”

The Free School adventure playground on Acklam Road was founded by Michael

X, with a Gustav Metzger auto-destructive art performance; basically

local kids burning a pile of rubbish. Metzger was part of the Fluxus

avant-garde art movement, which included Yoko Ono and influenced Hendrix

and the Who’s guitar smashing stage acts. While the Acklam adventure

playground experience influenced Pink Floyd’s 1979 single ‘Another

Brick in the Wall’, as portrayed in the video’s Gerald Scarfe

animation, Roger Waters and Dave Gilmour both acquired local brick piles.

As well as Notting Hill Carnival, Pink Floyd, the blob lightshow and

adventure playgrounds, the London Free School launched the UK underground

press, and the rave concept of clubbing on the world, from All Saints

hall. ‘International Times’, or ‘IT’, the first

and longest running British hippy underground paper, was a continuation

of the Free School newsletter; alternately titled ‘The Gate’

and ‘The Grove’. But, again largely via Hoppy, IT was inspired

by the US underground press; the 50s Village Voice, the East Village

Other, LA Free Press and the Berkeley Barb. The IT logo was the face

of the 20s Hollywood ‘it girl’ Clara Bow – by mistake,

it was meant to be Theda Bara. Taking the term ‘underground’

from wartime resistance groups was pushing it, but the hippies were

persecuted by the authorities, unlike all ‘underground’

pop cults since. They also had George Orwell’s typewriter, donated

by his wife Sonia, on which (in underground legend at least) he typed

‘1984’. The first issues featured the usual suspects; Michael

X, Alex Trocchi, Yoko Ono, Gustav Metzger, Timothy Leary, William Burroughs,

Allen Ginsberg, the black comedian Dick Gregory, and the McCarthy witch

trials saboteur Harvey Matusow.

IT and Pink Floyd were inaugurated with an ‘all night rave’

at the Chalk Farm Roundhouse, also featuring Soft Machine and a West

Indian steel band, then Hoppy and Joe Boyd launched the ‘Night

Tripper’/UFO psychedelic nightclub, on Tottenham Court Road; to

finance IT and as a larger venue for Pink Floyd to expand into from

All Saints Hall. As well as being the first modern nightclub, UFO (‘Unlimited’

or ‘Underground Freak Out’) was a proper radical club. While

Pink Floyd, Hendrix, Soft Machine, Arthur Brown and Procul Harum played,

accompanied by experimental theatre, films and lightshows, plans were

made for the underground press, the Arts Lab, legalising pot and, as

Miles recalled, “various schemes for turning the Thames yellow

and removing all the fences in Notting Hill.”