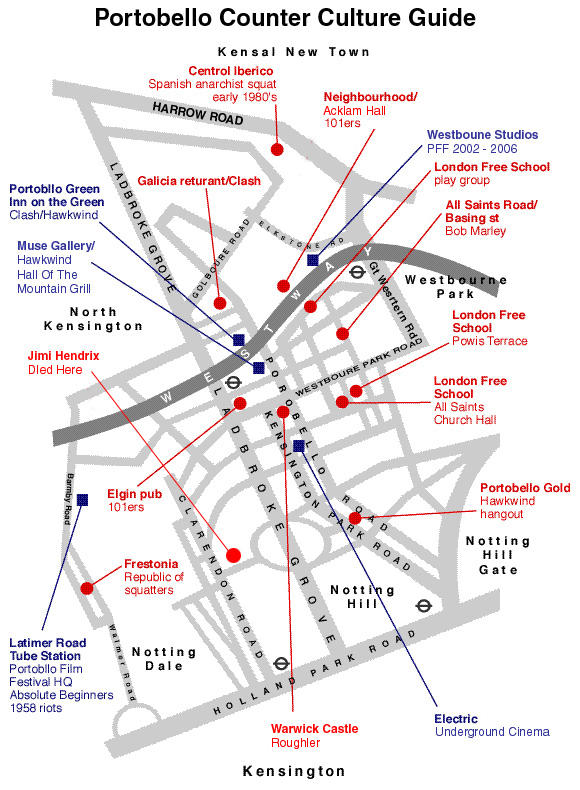

PORTOBELLO FILM FESTIVAL 2006

Counter Culture Portobello

Psychogeographical History

by Tom Vague.

Back to main

page

Part 2 - THE

LONDON FREE SCHOOL

Part 3 - HAWKWIND

Part 4 - BOB MARLEY AND THE WAILERS

Part 5 - STRUMMERVILLE

Part 6 - FRESTONIA

Part 7 - SKETCHES OF SPAIN

1 ABSOLUTE BEGINNERS

‘The kids live in the streets – I mean they have charge

of them, you have to ask permission to get along them even in a car

– the teenage lot are mostly of the Ted variety.’ Colin

MacInnes introduces Notting Hill, as ‘Little Napoli’, the

pop dystopia of ‘the Absolute Beginner’, our tour guide

on the ‘scenic railway ride’ through the 1958 white riot.

As Britain emerged from post-war austerity, working class youths found

themselves with money and time on their hands, no longer categorised

as older children or young adults but as a new economic class: the teenager.

The first British manifestation of the teenager, the Teddy boy, evolved

from the black spiv as a mutant hybrid of upper class Edwardian and

Wild West styles. This consisted of a quiff and greased back DA (duck’s

arse) hairstyle, drape coat, bootlace tie, drainpipe trousers, and brothel-creeper

or winkle-picker shoes. Having originated in Elephant & Castle,

the Teds first hit the headlines in the mid 50s when Bill Haley and

the Comets’ ‘Rock Around the Clock’ caused a rock’n’roll

moral panic. As they progressed from slashing cinema seats to harassing

West Indian immigrants, the Ted look caught on in Notting Hill, particularly

on Southam Street in Kensal while Notting Dale was rocking anyway. Regardless

of pop trends, the old slum area around Latimer Road station was in

a permanent riot-waiting-to-happen state.

In answer to the question, ‘if you’re so cute, kiddo, why

do you live in such an area?’, ‘the Absolute Beginner’,

first teenager, explained that firstly it was cheap, ‘but the

real reason, as I expect you’ll have already guessed, is that,

however horrible the area is, you’re free there!… And what

is more, once the local bandits see you’re making out, can earn

your living and so forth, they don’t swing it on you in the slightest

you’re a teenage creation… If you go in anywhere, they take

it for granted that you know the scene. If you don’t, it’s

true they throw you out in pieces...’ The advent of the teenager

coincided, not very happily, with the arrival of the first major wave

of West Indian immigrants. In ‘Windrush: The Irresistible Rise

of Multi-Racial Britain’ Mike Phillips portrays the hustlers or

rude boys (West Indian spivs) as the Wild West 11 frontiersmen, while

the Teds and fascists ironically assumed the native Red Indian role:

‘For some the Grove was a testing ground in which they lived wild

and free, uninhibited by laws and respectability… It was only

in Notting Hill that there was a public life. Clubs, restaurants, cafes,

music, street corner talk. This was the work of the immigrants, many

of them bad boys who set out to make Notting Hill a playground where

bad boys could have fun.'

On the foundation of the existing redlight

district, such frontier legends as ‘Two-gun Cassidy’ and

‘Weatherman’ established the black underworld, dressed in

Zoot suits and broad-brimmed hats. The early 50s black experience in

Notting Hill, Soho and the east end is chronicled in the rest of the

Colin MacInnes trilogy, ‘City of Spades’ and ‘Mr Love

and Justice’, and first hand in Sam Selvon’s ‘The

Lonely Londoners’. Michael de Freitas, the most notorious hustler

to emerge from the 50s Notting Hill scene, developed the street style

through the 60s, from ‘black Rachman’ ghetto superstar into

Black Power X-cess. The scene originally revolved around Totobag’s

Café, just off Portobello at 9 Blenheim Crescent; now a market

store that looks like it’s preserved in its 50s state as a memorial

to the Absolute Beginners. Also known – not always metaphorically

– as ‘The Fortress’, the cafe acted as a proto-community

centre/information bureau for newcomers, gambling den/dominos venue

to such sound-system pioneers as Baron Baker, Count Suckle, Duke Vin

and King Dick, slumming attraction to bohemian girls like Sarah Churchill

(Winston’s favourite actress daughter) and cool hangout of white

hipsters like Georgie Fame and Colin MacInnes.

As black people gradually established a presence in Notting Hill pubs;

like the Colville (known affectionately as ‘The Pisshouse’,

now the Ground/First Floor bar/restaurant) and the Apollo on All Saints

Road (now studios); with most local hostelries unwelcoming (to anyone,

regardless of race, who wasn’t local), the hustlers developed

their own scene. In an attempt to recreate back-a-yard sound-system

culture in an indoor London setting, this consisted of various types

of clubs; ‘after-hours’ or ‘afters’ drinking

clubs, basement/cellar-clubs or clip-joints – for daytime gambling,

rent-parties – where resources were pooled to pay off landlords

or buy houses, and the most famous, ‘blues’ – dances,

clubs or parties – named not after blues music but in honour of

the Blaupunkt (‘Blue Point’ or ‘Blue Spot’)

radio-gramophone; the prototype sound-system. Blues dance music went

from jazz, calypso and Jamaican rhythm’n’blues, through

ska and rocksteady to 70s dub reggae.

Like Irish shebeens (as West Indian clubs were also known), and the

original (and most violent) mushroom clubs of the indigenous English,

blues could crop up anywhere but tended to be in the Rachman areas around

Powis Square and St Stephen’s Gardens. The story of the blues

began in the basement of Fullerton the tailor’s on Talbot Road,

where Duke Vin was the selector, then Bajy opened a café and

cellar club next door. (Fullerton’s went on to be Coin’s

café, and now Raoul’s restaurant, while Bajy’s became

the Globe, Roy Stewart’s celebrated bar/restaurant). Around the

corner, on Powis Square, Michael de Freitas’s basement Rachman

flat boasted a residency by the jazz pianist Wilfred Woodley. Colville

Terrace had Sheriff’s club/gym and the Barbadians’ club,

the exclusive Montparnasse was further along Talbot Road. On Westbourne

Park Road there was the Number 51 gambling club, Larry Ford’s

club Fiesta One on the corner of Ledbury Road, and the Calypso club

near St Stephen’s Gardens. Thus defining the original, more Westbourne

than Ladbroke, West Indian Grove.

The soundtrack of 1958 was ‘Johnny B Goode’ by Chuck Berry,

‘Breathless’ by Jerry Lee Lewis, ‘Summertime Blues’

by Eddie Cochran, ‘Rave On’ by Buddy Holly, ‘Rebel

Rouser’ by Duane Eddy, and ‘Rumble’ by Link Wray.

The Absolute Beginner first hears news of race rioting in Nottingham

(the week before Notting Hill kicked off) as he’s leaving a ‘Maria

Bethlehem’ (Ella Fitzgerald) concert. On a multicultural jazz

high, he dismisses it with cosmopolitan disdain, ‘but what could

you expect in a provincial dump out there among the sticks.’ The

first teenager’s friends include ‘Mr Cool’, a black

jazz trumpet player, the gay ‘Fabulous Hoplite’, the lesbian

madame ‘Big Jill’, and rival trad and mod jazz enthusiasts

who join forces against the Teds and fascists. Yet, as the black and

white ‘young and restless were creating a new world of cool music,

coffee bars and freer love’ in Soho, over in White City the London

version was beginning. In the first incident a gang of youths drove

around Shepherd’s Bush and Notting Hill attacking any black people

they came across. After that racial tension increased, unchecked by

the authorities, and encouraged by the fascists. A week later the suspected

house of a West Indian pimp on Bard Road and a blues party on Blechynden

Street were attacked by a local mob, setting off the late August riot

weekend.

‘Jungle West 11’, the pulp fact book by Majbritt Morrison,

features the attack on the Blechynden Street blues (in W10) that started

the riot weekend. The same incident, recalled by King Dick in 'Windrush',

consisted of Count Suckle playing the calypso record ‘Oriental

Ball’, mixed with the bee swarm sound of the Latimer Road mob

approaching, shouts of “Keep Britain White!”, breaking glass

and police sirens. On this occasion police escorted the West Indian

partygoers out of the Dale, to another club east along Lancaster Road.

However, this gave the mob the impression that they could ‘ethnically

cleanse’ the area. The first Notting Hill Carnival, in the ‘riotous

revelry: reckless indulgence in something eg. bloodshed’ definition,

largely consisted of the Latimer Road mob drunkenly milling about under

the railway arches. The Kensington News reported locals in the pubs

of Notting Dale singing ‘Old Man River’ and ‘Bye Bye

Blackbird’, punctuated by ‘vicious anti-negro slogans’.

While the moment in pop history was summed up by Colin MacInnes, another

Colin – Eales, the News reporter – is cited in 'Windrush'

for capturing ‘the precise flavour of street corner agitation,

incredible rumour, sexual hysteria, random violence and holiday anarchy.’

‘Sapphire’, Basil Dearden’s 1959 follow up to ‘The

Blue Lamp’, examines racial prejudice during the course of an

investigation into the murder of a light-skinned West Indian girl. The

black suspect, ‘Johnny Fiddle’, escapes the law from the

‘Tulips Club’ in Shepherd’s Bush, where everyone’s

called Johnny something, only to run into Notting Dale. There he’s

beaten up by Teds under the Latimer Road arches, and saved by a grocer

woman locking him in her shop until police arrive; re-enacting a real

riot incident also incorporated into ‘Absolute Beginners’.

In the end ‘Johnny Rotten’ turns out to be the mad racist

sister of the victim (Sapphire)’s white boyfriend.

On Day 3 of the riots, Monday September 1, once sufficiently encouraged

by the fascists, the mob rampaged across Ladbroke Grove to besiege Rachman’s

black ghetto. By then traditionally rival gangs from Shepherd’s

Bush, Hammersmith and Paddington were there amongst the spectators.

But it was at this point that the riot dynamic, between the older generation

and the Teds, came apart. At first, the former were said to give tacit

approval of the latter’s behaviour, but the arrival of outsider

hooligans and tourists caused some locals to have regrets and even empathise

with local blacks. One told the Kensington News: “In too many

cases innocent blacks are getting beaten when it’s the rotten

ones that’s still running about.” Michael de Freitas recalled

actively taking part in the riot; freeing arrested hustlers from a Black

Maria and petrol-bombing a white drinking club; but, rather than the

police or locals, he blamed ‘the irresponsible journalism which

exaggerated a few isolated incidents into large scale racial disturbances.’

In the ‘Absolute Beginners’ film footnote to the book, Gary

Beadle (as ‘Johnny Wonder’) portrays Michael – on

his way to becoming Michael X – as he organised the black resistance

at the Calypso Club on Westbourne Park Road. This involved turning Totobag’s

into a real fortress, from which white rioters were repelled with Molotov

cocktails. The 1958 battle of Blenheim Crescent was re-enacted by Julien

Temple in 1985, dramatised as MacInnes intended it to be, as a ‘West

Side Story’-style dance sequence – Jet/Capulet hustlers

v Shark/Montagu fascists – on a set at Shepperton Studios, combining

the Blenheim Crescent and Bramley Road riot zones. As Temple told the

NME in the 80s: “I don’t think they’d let you stage

a race riot that easily in Notting Hill these days, and the place

itself has all been painted in pretty electric blues or apricot and

pink, whereas in the 50s it was all crumbling and blackened slums.”

Totobag’s has in recent years been overshadowed by its Hollywood

W11 neighbour, the Travel Bookshop at 13/15 Blenheim Crescent, also

recreated – at 142 Portobello Road – in the 1998 ‘Notting

Hill’ film.

The Daily Mail duly came up with a cartoon of Teds trampling on a British

flag, and the government announced short-sharp-shock measures to ‘de-Teddify

the Teddy boys’. Of the 100 men arrested over the riot weekend

(including Michael, for obstruction) 75% were white, and 60% under 20;

and some were of the Ted variety. However, as Edward Pilkington puts

it in ‘Beyond the Mother Country: West Indians and the Notting

Hill White Riots’, ‘it is not at all clear that the rioters

were exclusively, or even primarily, Teddy boys.’ In all first

hand accounts the Teds were encouraged by the fascists to fit themselves

up, as empire throwback scapegoats, and take the blame on behalf of

the older locals and the authorities. Locals quoted by Pilkington, and

elsewhere, play down their importance: “A couple of them were

what you might call Teddy boys, but the others, they were hard-working

lads… The Teddy boys jumped on the bandwagon… It was the

older generation who started it.” By 1958 Teddy boy had become

the generic term for juvenile delinquent, and was applied to all teenage

hooligans regardless of fashion. They’ve since been, if not vindicated,

put into perspective as merely the hoody equivalent hooligans of the

day. In ‘Absolute Beginners’ ‘Ed the Ted’ is

mostly just gormless, as definitively portrayed by Tenpole Tudor in

the film.

George Melly defined the Teds’ revolt into style as an economic

development from the spivs: ‘They were not criminal in the

old sense. They were not out for gain. On the whole, though, they were

profoundly anti-social: the dark van of pop culture, dedicated to the

giggle and kicks.’ Julien Temple, promoting his ‘Teenage’

project in the NME in 1985, went further, eulogising the Teds as “like

something out of the Wild West, they were villains, but really they

were epic in that context… They were an epic breed, Byronic in

their scope, most of all they frightened the establishment. They were

much bigger and more dissenting than rock’n’roll. They are

a part of the despair of Britain after the hopes of the end of the war.”

Encouraged by the riots, and the Teds’ support, the fascist leader

Oswald Mosley made his last comeback attempt, standing as the Union

Movement candidate for North Kensington in the 1959 election. In Trevor

Grundy’s ‘Memoir of A Fascist Childhood’ hundreds

of Teds followed the Leader to his street meetings. Mosley’s sons

Alex and Max (the future Formula 1 motor racing leader) canvassed among

them, posing for the Daily Mirror as actual upper-class Teds. As the

Mosley Youth leader, Grundy fought a losing battle for the hearts and

minds of the Teds, with Elvis. ‘The Wizard’ pimp/fascist

character, representing ‘the dark side of the teenage dream’

in ‘Absolute Beginners’, was based on youths who told the

press: “So a darkie gets chivved, why all the fuss?… Come

back tomorrow night, mister, for the next instalment.” Whereas

the first and worst local graffiti, ‘Keep Britain White’;

initialised as ‘KBW’, and accompanied by Mosley's flash

and circle symbol; was by fascist youths like Grundy and Max Mosley,

not local Teds. ‘It Happened Here’, Kevin Brownlow and Andrew

Mollo’s occupied London documentary-style film, contains a scene

where Nazi officers are attacked by local resistance fighters, in the

beergarden of the Prince of Wales, on Pottery Lane. When, in reality,

at the time of filming in the late 50s and early 60s neo-nazis were

getting the pints in for the locals.

Summing up the times, ‘the first teenager’ concluded: ‘What

an age it is I’ve grown up in, with everything possible to mankind

at last, and every horror too, you could imagine! And what a time

it’s been in England, what a period of fun and hope and foolishness

and sad stupidity!’ Colin MacInnes predicted that the riots would

mark the end of Britain’s claim to moral leadership of the world,

as ‘Absolute Beginners’ began British pop world domination.

Richard Wollheim, in his ‘Babylon, Babylone’ review of the

pop style bible, described it as the blueprint for the future teen age,

and the first mods as the new dandy aristocracy. For the mod cover photograph

of the first edition, MacInnes called Roger Mayne, the somewhat older,

real local photographer hero. Mayne returned to Southam Street in Kensal,

where a West Indian had been stabbed to death during ‘the ugly

election’, and Mosley subsequently held a meeting. Rather than

start another riot, the killing of Kelso Cochrane turned the tide against

the fascist leader, and caused the evaporation of his local support.

At least when posing on the Mayne Road, Teds and hustlers seem to have

co-existed amicably enough.

‘Absolute Beginners’ stars Patsy Kensit as the Juliet beat

girl ‘Crepe Suzette’, Ray Davies (of the Kinks) and Mandy

Rice-Davies (of the Profumo affair) as the parents of the Absolute Beginner

(‘Colin’ in the film), played by Eddie O’Connell.

Sade appears as Billie Holiday (rather than Ella Fitzgerald), Steven

Berkoff as Mosley, Sandie Shaw as ‘Baby Boom’s mum’,

Alan Freeman and Lionel Blair, basically as themselves, ditto Bowie

as the ad executive. Tim Roth was in the running for the lead role while

Keith Richards was to play a ‘music hall cheeky chappie’,

and Richard Branson dressed as a Ted at the premiere. The soundtrack

features Gil Evans, Laurel Aitken’s ‘Landlords and Tenants’,

Tenpole Tudor’s ‘Ted Ain’t Dead’, Clive Langer’s

‘Napoli’, Jerry Dammers’ ‘Riot City’,

Bowie’s title track and Smiley Culture’s electro-‘Absolute

Beginners’ mix of the ’58 Miles Davis hit, ‘So What’.