PORTOBELLO

CARNIVAL FILM FESTIVAL 2008

1

Portobello Carnival Film Festival 2008

2 Lord

Holland’s Slavery to Work Scheme

3 The

Notting Dale Gypsies

4 Portobello

Busker Parades

5 1966

London Free School Michaelmas Fayre

6 1968

Interzone International Times Fair

7 1977

Two Sevens Clash Punky Reggae Party

8 1983/4

Aswad Live And Direct Carnival

9 1995

Hugh Grant Mas and Mayhem

PART 6

1968 Interzone International

Times Fair

‘Walking the

Grove’ in the May ’68 ‘Interzone’

International Times, Courtney Tulloch concluded that

‘Notting Hill in its social aspects – housing

and so on – is a huge grimy garbage heap, that

is just waiting to get set on fire… In the meantime,

look forward to the Notting Hill Fair especially, a

human bonfire of energy and colour. Don’t wait

for the area to change – no change in a physical

environment how ever great can ever change you. Instead

dig the vibrations in and around Notting Hill, perhaps

the only area in London where through the differing

enclaves of experimental living, a free-form and ingenious

communal life-style could really burst forth... Now

there are signs that a real underground community is

alive, and especially in the village around Portobello

Road, down to the Gate. Each person will carry a fire

in their heads despite (perhaps because of) the garbage,

the ghetto poverty and the rest.’

1969 King Mob Situationist Carnival

The year of ‘Getting It Straight In Notting

Hill Gate’ by Quintessence, the Situationist King

Mob group presented a ‘Miss Notting Hill ’69’

Carnival float, featuring a girl with a giant syringe

attached to her arm. This was ‘a comment on the

fact that there was junk and junk, the hard stuff, or

the heroin of mindless routine and consumption.’

1970 Notting Hill People’s Free Carnival

The weekend before the 1970 Notting Hill Fair/Carnival,

Mick Farren and the Pink Fairies represented the Grove

at a demo in Trafalgar Square, in solidarity with ‘East

End squatters, Notting Hill blacks, and Piccadilly freaks.’

The next day Hawkwind headlined a space-rock skinhead

moonstomp on Wormwood Scrubs. Ironically, as the voice

of the black community began to be heard at the start

of the 70s, if anything Notting Hill Carnival became

more of a hippy festival. After Rhaune Laslett’s

original Carnival committee pulled out due to the racial

tension in the area in the wake of the first Mangrove

bust, the radical street hippies took over. The 1970

Notting Hill ‘People’s Carnival’ consisted

of a procession round the area, starting and finishing

in Powis Square, led by Ginger Johnson’s African

drummers and a witchdoctor. Proceedings ended with a

rock festival in the square gardens featuring the American

band Socca/Sacatash, Mataya, Stackhouse, James Metzner

‘and various local musicians.’

1971 Angry Hippy Carnival

In the run-up to the Angry Notting Hill Carnival

of 1971, Frendz made ‘a call to all progressive

people; black people smash the racist immigration bill;

workers of Britain smash the Industrial Relations bill.

All progressive people unite and smash growing fascism.

Rally and march July 25, Acklam Road, Ladbroke Grove

2pm. Black Unity and Freedom Party.’ On the gatefold

sleeve of Hawkwind’s 1971 album ‘X In Search

of Space’, designed by Barney Bubbles, the group

are pictured playing a free gig under the Westway. That

summer Hawkwind appeared on several occasions at different

locations under the flyover, including the Westway Theatre

on the site of the Portobello Green Arcade and to the

east (where Neighbourhood nightclub would later appear).

These gigs were usually benefits for local causes, during

which they would merge with the Pink Fairies as Pinkwind.

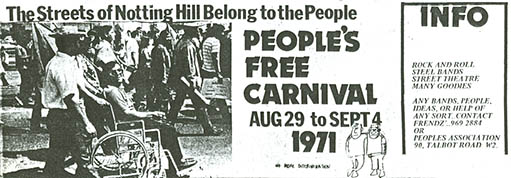

The underground press ad for the ‘People’s

Free Carnival August 29 – September 4 1971’

proclaimed: ‘The Streets of Notting Hill belong

to the people – rock’n’roll –

steel bands – street theatre – many goodies

– any bands, people, ideas, or help of any sort,

contact Frendz or People’s Association, 90 Talbot

Road W2.’ The FreeFrendz ‘Blow Up’

Angry Brigade special reported that the ‘People’s

Carnival got off to a joyous start. The street fest

continues all this week so do it in the road as noisily

as you can.’ The Pink Fairies were pictured amongst

the kids in the Powis Square gardens, ‘at a quieter

moment during the Notting Hill Free Carnival, a fantastic

week of music, theatre and dancing in the street. Everybody

got it on and the streets really came alive.’

Pictures of Mighty Baby and Skin Alley playing on the

site of Portobello Green were captioned: ‘The

weekly Saturday concert under Westway in Portobello

Road pounds on. Next week Graham Bond, Pink Fairies

and Hawkwind.’

The local street hippies Skin Alley told Frendz of an

anti-common market demo in Powis Square, with Julie

Driscoll and some ‘very far out modern jazz trios’

who didn’t go down too well with the kids. Powis

Square, during the 1971 Carnival, was also the unlikely

venue of the debut with Hawkwind of the former Hendrix

roadie, Ian ‘Lemmy’ Kilmister (or Kilminster),

later of Motörhead. The Carnival procession consisted

of a steel band led by Merle Major, an angry West Indian

mother of 6, chanting “Get involved, Power to

the People”; from her old house on St Ervan’s

Road to Powis Square, where the People’s Association

had opened a squat for her. As an effigy of her landlord

was burnt, Merle Major sang the ’71 Carnival hit,

‘Fire in the Hole’, which included the line,

‘the people of the borough pay for your car.’

The Angry Carnival HQ on Talbot Road was subsequently

busted by the bomb squad.

1972/3 Calypso Carnival

From the early to mid 70s, under the administration

of the Trinidadian Leslie Palmer, the Notting Hill hippy

‘fayre’ was transformed into ‘an urban

festival of black music’, based on the Trinidad

Carnival model. From the first Carnival HQ on Acklam

Road, Leslie Palmer established the blueprint of the

modern event; getting sponsorship, recruiting steel

bands and sound-systems, introducing generators and

extending the route. The attendance went up accordingly

from 3,000 at the beginning of the 70s to 50,000 in

1973.

1974/5 Reggae Carnival

By the mid 70s, Jamaican reggae was challenging

Trinidadian calypso’s dominance of Notting Hill

Carnival. At the 1974 flares and platforms Carnival,

the Trinidadian organiser Leslie Palmer introduced reggae

sound-systems and the Cimarons played, thus attracting

black youth from all over London, rather than just locals.

In 1975 the turnout reached 100,000, and the Carnival’s

press profile changed from harmless hippy fair to public

order problem. Back in Trinidad, as Michael X was executed,

the calypsonian Black Stalin sang: ‘Go rap to

them baldhead, tell them, calypso gone dread.’

1976 Carnival Police Clash

In 1976, as Darcus Howe’s militant Carnival committee

and the Golborne 100 group (led by George Clark, the

1967 Summer Project saint-turned-anti-Carnival sinner)

joined the fray, as well as the Clash there were 1,500

white men in uniform in Notting Hill. In the Armagideon

Times fanzine ‘Story of the Clash’, Joe

Strummer recalled getting caught up in the first incident

under the Westway. After a group of ‘blue helmets

sticking up like a conga line’ went through the

crowd, one was hit by a can, immediately followed by

a hail of cans:

‘The crowd drew back suddenly and the Notting

Hill riot of 1976 was sparked. We were thrown back,

women and children too, against a fence which sagged

back dangerously over a drop. I can clearly see Bernie

Rhodes, even now, frozen at the centre of a massive

painting by Rabelais or Michelangelo… as around

him a full riot breaks out and 200 screaming people

running in every direction. The screaming started it

all. Those fat black ladies started screaming the minute

it broke out, soon there was fighting 10 blocks in every

direction.’ Joe later recalled failing to set

a car alight with a box of matches along Thorpe Close.

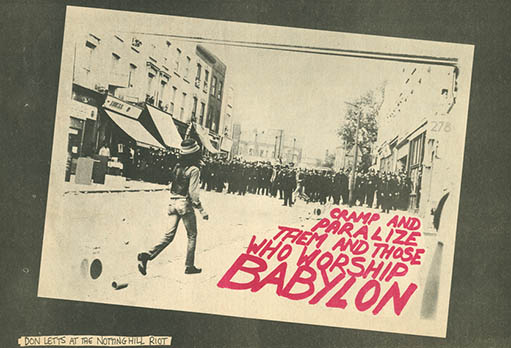

Meanwhile on Portobello Road, Don Letts (the future

Clash associate film director) was walking into pop

history towards Acklam Road – passing the Black

People’s Information Centre sound-system/disco

unit, hippies looking out of the upstairs windows of

numbers 305 to 9, and a line of policemen – as

Rocco Macaulay began taking his famous series of pictures

of the next charge. Macaulay’s shot of police

reaching the Westway, where the black youths had gathered

(now the Portobello Green arcade) duly became the back

cover of ‘The Clash’ album and the ‘White

Riot’ tour backdrop projection. Don Letts’

Wild West 10 walk first appeared on the sleeve of the

‘Black Market Clash’ mini-LP in 1980.

As the riot raged under the Westway, alongside hoardings

sprayed with ‘Same thing day after day –

Tube – Work… How much more can you take’,

with the youths being driven up Tavistock Road towards

All Saints Road, in what could be an apocryphal report

a drunk staggered between the police and youth lines,

causing hostilities to temporarily cease until he stumbled

off over a wall. Later that night, Joe Strummer, Paul

Simonon and Sid Vicious were warned off by a black woman

when they attempted to enter the West Indian Metro youth

club on Tavistock Road.

The Sun’s ‘Carnival of Terror’ feature

included the Sun ‘man on the spot’ reporting

on ‘How I was kicked at Black Disco’ –

Acklam Hall under the Westway (on the site of 12 Acklam

Road/Neighbourhood nightclub). The reggae promoter Wilf

Walker remembers Acklam Road in ’76 as a spiritual

awakening of black Britain: “It was incredible

in those days to be in a sea of black faces. As a black

person, that kind of solidarity we don’t experience

anymore… We described it as a demo of solidarity

and peace within the black community. I can’t

imagine what it would have been like for white people…

’76 showed the strength of feeling, reggae was

raging in those days, young blacks weren’t into

being happy natives, putting on a silly costume and

dancing in the street, in the same street where we were

getting done for sus every day.”

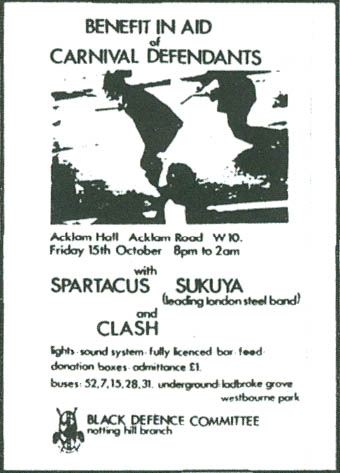

Wilf Walker’s Acklam Hall punky reggae party began

with a Black Defence Committee benefit ‘in aid

of Carnival defendants’; featuring Spartacus R

(from Osibisa), the Sukuya steel band, and ‘Clash’

were billed (with no ‘The’) but didn’t

actually play. As Joe Strummer told the NME, “It

wasn’t our riot, though we felt like one.”

Although the Clash already existed, it can be argued

that they were a pop culture echo of the 1976 riot,

like Absolute Beginners was of 1958. Marcus Gray calls

it ‘the catalyst that brought to the surface a

lot of disparate elements already present’ in

the group. Not least, they got into reggae, feeding

dub effects, ‘heavy manners’ stencil graffiti

and the apocalyptic Rasta rhetoric into the mix.

The NME reggae buff Penny Reel cites the Dennis Brown

tracks ‘Wolf and Leopard’, ‘Whip them

Jah’ and ‘Have No Fear’ as portents

of ‘War inna Babylon’, played by Lloyd Coxsone

under the Westway and Observer Hi-fi on Kensington Park

Road (outside the newly opened original Rough Trade

shop) in ’76. In the reggae riot response, the

Pioneers lamented the ‘Riot in Notting Hill’

on Trojan, the Trenchtown label came up with ‘Police

Try Fe Mash Up Jah Jah Children’ by Mike Durane,

and the Morpheus label had their own militant take on

‘Police and Thieves’, ‘Police and

Youth in the Grove’/‘Babylon A Button Ladbroke

Dub’ by Have Sound Will Travel (promoted with

a punky riot headline flyer). Aswad had already recorded

‘Three Babylon’ (‘Three Babylon tried

to make I and I run, they come to have fun with their

long truncheons’) about a police incident under

the Westway before the ’76 riot.

7 1977

Two Sevens Clash Punky Reggae Party

|